What Are **Pasted Valve Bags**? Definitions, Synonyms, and Why They Matter

Paper valve sacks used for powders in construction are widely known as **Pasted Valve Bags**. They are multi‑wall paper sacks with a pre‑formed valve opening that mates with a packing spout, and with seams and bottoms bonded by adhesive rather than stitching. Colloquial aliases include paper valve sacks, cement valve bags, valve paper bags, and multiwall pasted valve sacks—different names, one essential idea: a self‑locating short sleeve at the corner or mouth that allows rapid, controlled filling while the sack itself vents entrained air through the paper structure (and, when specified, micro‑perforations). After dosing, the valve either self‑closes because of product pressure or is sealed with a short thermal, ultrasonic, or hot‑melt step, creating a compact, clean package.

Why this format and why now? Because building material supply chains are pressured by speed, worker protection, and moisture management—all at once. A bag that fills quickly, stacks stably, communicates clearly, and guards product quality across humid routes must balance physics (de‑aeration), chemistry (fibre and film selection), and human factors (ergonomics and print legibility). The valve sack, in its modern form, grew precisely to reconcile those demands.

Materials and Architecture of **Pasted Valve Bags**: From Fibres to Films

Every specification decision—paper grade, film gauge, valve patch, glue type—nudges performance in filling speed, dust control, moisture resistance, and recyclability. The core structure remains consistent: a multi‑ply paper tube, a reinforced valve corner, and pasted cross‑bottoms. Yet inside that simple sketch lives a system of trade‑offs.

Think of **Pasted Valve Bags** as a stack of functions masquerading as a single package: the outer ply communicates and grips; interior plies carry load; optional films guard against moisture; the valve mediates between dynamic air and dense powder. Reduce any one element and the others must respond—less film means more attention to paper porosity and spout extraction; higher drop requirements may push TEA targets or bottom glue maps.

Characteristic Advantages of **Pasted Valve Bags**: Speed, Cleanliness, Integrity

Why do plants lean toward this format when handling cement, gypsum, grout, and polymer‑modified mortars? Because the core virtues reinforce each other: fast filling reduces operator exposure; stable pack geometry reduces transport losses; clear printing reduces site mistakes. The package is not just a vessel; it is a workflow component.

- High‑throughput spout filling: the valve aligns, vents, and closes—especially when paired with high‑porosity papers—so cycles are short and dosing accuracy holds.

- Lower ambient dust: air can exit through the wall rather than back‑blowing at the operator; post‑fill seals limit sifting during warehouse handling.

- Moisture awareness by design: thin, targeted barrier elements preserve shelf life without turning the sack into a slow‑filling, air‑trapping container.

- Robust pallet behaviour: cross‑bottom geometry and anti‑skid patterns bolster stack compression and truck‑route survivability.

- Brand and compliance surface: wide printable panels carry batch codes, safety pictograms, and usage instructions that remain legible through transit.

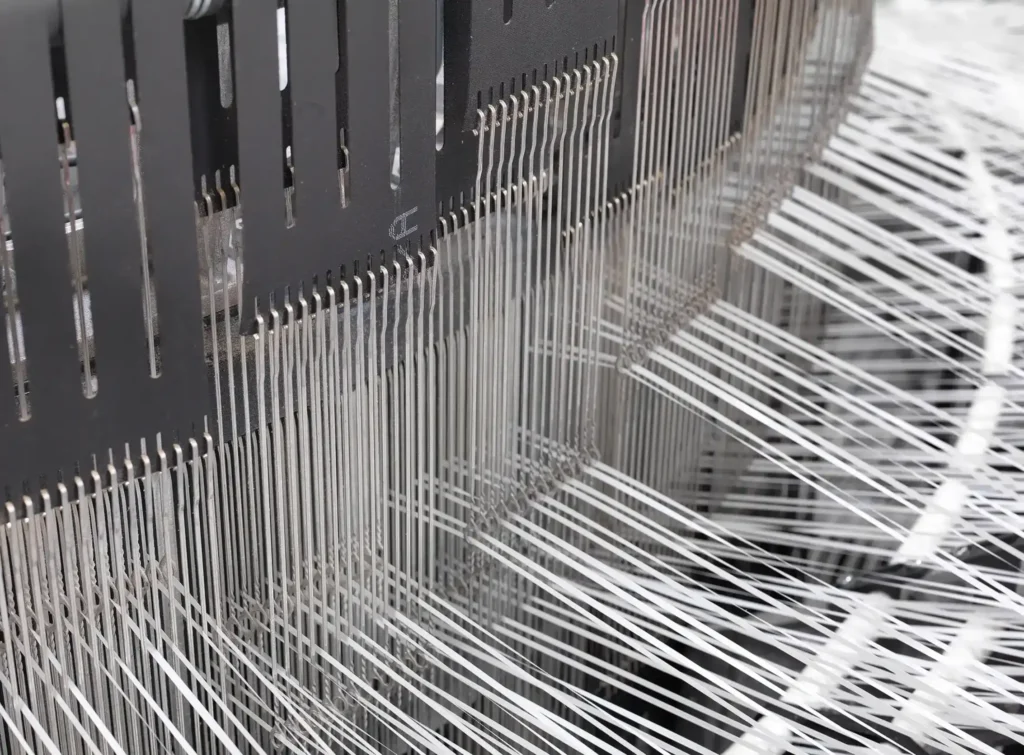

Production Flow of **Pasted Valve Bags**: From Roll Stand to Flat Sack

- Paper preparation: sack kraft reels in designated grades and basis weights are staged with automatic splices; tension and moisture are controlled to keep caliper and runnability stable.

- Flexographic printing: the outer ply receives graphics using water‑based inks; anti‑skid patterns can be zoned along intended contact faces.

- Tubing and side seam pasting: multiple webs are combined into a multi‑wall tube with adhesive seams; valve corner die‑cuts and patches may be applied inline.

- Bottom formation: cross‑bottoms are folded and pasted with engineered glue maps for strength and low sifting; dimensions are held tightly to support pallet regularity.

- Liner insertion and valve finishing (if specified): a short PE cuff or laminated ply is added for barrier continuity; external sleeve designs prepare for heat sealing at the packer.

- Inline quality control: vision systems verify glue lines, valve openings, and geometry; samples undergo drop and air‑leak tests.

- Counting and bundling: flat sacks are stacked, interleaved, and stretch‑wrapped for shipment to the filling plant.

Applications of **Pasted Valve Bags** Across Building Materials

The portfolio is broad: ordinary Portland cement, white cement, limestone or slag blends, dry mortar, tile adhesives, grouts, gypsum plaster, hydrated lime, fly ash and mineral powders, self‑levelling compounds, repair mortars. Each product family presses on a different knob—flow, air entrainment, moisture sensitivity—and the sack responds with paper porosity, valve style, and barrier placement.

| Powder | Flow Behavior | Moisture Sensitivity | Typical Sack Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Portland cement | Free‑flowing | Medium | 2–3 plies with high‑porosity outer; internal self‑closing valve; minimal micro‑perfs |

| Fine low‑carbon blends | More air entrained | Medium | 3‑ply, ultra‑breathable outer; external heat‑sealable valve; optional thin barrier |

| Gypsum plaster | Free‑flowing to cohesive | High | 2–3 plies; inner barrier via cuff or laminate; high‑porosity outer |

| Tile adhesive / polymer‑modified mortar | Cohesive | Medium–High | 3‑ply; wider sleeve; air or screw packer; heat‑seal valve patch |

Notice the pattern: as powders get finer or more polymer‑rich, the specification gravitates toward higher porosity, external heat‑sealed valves, and smarter barrier placement. As ambient humidity rises, thin films or liner cuffs come into play, but never at the expense of filling speed if it can be helped.

System Thinking with **Pasted Valve Bags**: Linking Powder, Paper, Valve, and Machine

Consider a rhetorical question: when a bag “balloons” at the spout, is the culprit the paper, the powder, or the packer? The honest answer is often “all three.” De‑aeration is a chain; the slowest link sets the tempo. The package engineer, therefore, must choreograph materials science (porosity and TEA), process engineering (spout air, screw speed, impeller profile), and logistics realities (humidity, drop height, pallet overhang). Align the trio and the process sings; misalign them and even premium materials disappoint.

Key Parameters for **Pasted Valve Bags**: Ranges and Targets

| Parameter | Typical Range / Options | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Filling weight | 20–50 kg (25 kg and 50 kg common) | Ergonomics may favour 20–25 kg for heavy adhesives. |

| Dimensions (W × L × G) | 300–550 mm × 450–900 mm × 80–180 mm | Optimized for brick‑like pallet patterns. |

| Plies | 2–4 plies (one‑ply for ≤35 kg in some designs) | Balance drop resistance, porosity, and cost. |

| Paper basis weight | 60–100 g/m² per ply | High‑porosity or semi‑extensible grades common. |

| Valve type | Internal self‑close; external heat‑sealable; PE sleeve | Match to powder flow and sifting risk. |

| Barrier strategy | None; 8–30 µm films; short liner cuffs | Balance WVTR with de‑aeration speed. |

Cost and Value with **Pasted Valve Bags**: Where the Money Moves

Most of a sack’s unit cost lives in paper mass—basis weight × area × number of plies—so the prime lever is materials efficiency without sacrificing drop and compression performance. Choosing higher‑TEA papers can allow ply reduction; rationalizing print colours trims ink and drying windows; deploying a short heat seal post‑fill can save large downstream loss from sifting. And scrap on tubers and bottomers—set‑up waste, mis‑register, edge crack—quietly taxes each thousand sacks; stable paper caliper and moisture control are cheap insurance.

Troubleshooting **Pasted Valve Bags**: Symptoms, Causes, Countermeasures

Environmental and Regulatory Lens on **Pasted Valve Bags**

Two goals—material efficiency and fibre recovery—guide current design choices. Paper‑dominant constructions with minimal, easily separable plastics tend to fare best in recycling streams. Water‑based inks keep emissions low, while wet‑strength or barrier choices are justified when logistics dictate. The law of unintended consequences applies: a perfect moisture barrier that slows filling and raises dust would harm workers and throughput. Balance is the mandate.

Comparative Formats for Powder Packaging: When **Pasted Valve Bags** Are Not the Answer

There are valid alternatives. Form‑fill‑seal PE sacks excel for outdoor‑stored, highly moisture‑sensitive goods and granular resins; woven PP block‑bottom valve sacks offer formidable puncture resistance; pinch‑bottom open‑mouth bags provide premium graphics for pet food and similar markets. Yet each alternative introduces its own system requirements—different fillers, different venting strategies, different end‑of‑life pathways. The case for valve paper sacks remains strongest where powder de‑aeration speed, dust stewardship, and rectangular stacking dominate the requirement list.

Case Notes Using **Pasted Valve Bags**: Field‑Tested Adjustments

- Humid coastal export of white cement: switch from 3‑ply all‑paper to 2‑ply + 12 µm liner cuff and external sealable valve; add wet‑strength outer ply and anti‑skid zones; complaints of caking drop while fill speed holds.

- Tile adhesive with high polymer fraction: widen valve sleeve and use air packer; adopt heat‑sealed valve patch; dust at customer sites falls and dosing variance narrows.

- Light bulk density lime: external sleeve with robust seal plus ultra‑breathable outer ply; pallet stability improves after anti‑skid patterning and stricter bottom tolerances.

Working Glossary Around **Pasted Valve Bags**

For readers wanting a one‑stop reference page with product variants, see industrial valve bags (alternate anchor: valve paper bags), which provides a general look at the format and related offerings.

- What Are **Pasted Valve Bags**? Definitions, Synonyms, and Why They Matter

- Materials and Architecture of **Pasted Valve Bags**: From Fibres to Films

- Characteristic Advantages of **Pasted Valve Bags**: Speed, Cleanliness, Integrity

- Production Flow of **Pasted Valve Bags**: From Roll Stand to Flat Sack

- Applications of **Pasted Valve Bags** Across Building Materials

- System Thinking with **Pasted Valve Bags**: Linking Powder, Paper, Valve, and Machine

- Key Parameters for **Pasted Valve Bags**: Ranges and Targets

- Cost and Value with **Pasted Valve Bags**: Where the Money Moves

- Troubleshooting **Pasted Valve Bags**: Symptoms, Causes, Countermeasures

- Environmental and Regulatory Lens on **Pasted Valve Bags**

- Comparative Formats for Powder Packaging: When **Pasted Valve Bags** Are Not the Answer

- Case Notes Using **Pasted Valve Bags**: Field‑Tested Adjustments

- Working Glossary Around **Pasted Valve Bags**

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Technical Specifications: Thickness, Weight, and Size

- 3. Anti-Static Mechanisms: Safeguarding Hazardous Environments

- 4. Load Capacity and Durability Testing

- 5. Market Relevance and Case Studies

- 6. FAQs: Addressing Industry Concerns

- 7. Strategic Innovations and Sustainability

- 8. Conclusion

A Conversation with Ray, CEO of VidePak

Interviewer: “VidePak has become a global leader in woven bag manufacturing. How do pasted valve bags align with the demands of the building materials sector?”

Ray: “Pasted valve bags are engineered for precision and safety. Their anti-static properties, customizable thickness (80–150 GSM), and load capacity (up to 50 kg) make them indispensable for transporting cement, gypsum, and chemical additives. Combined with Starlinger’s technology, we ensure these bags meet rigorous industrial standards while reducing environmental risks.”

1. Introduction

The building materials industry relies on packaging solutions that balance durability, safety, and cost efficiency. Pasted valve bags, characterized by their sealed valve closure and anti-static features, have emerged as a critical component in transporting powdered and granular materials like cement, fly ash, and construction adhesives. VidePak, leveraging 30+ years of expertise and Starlinger’s advanced machinery, exemplifies how innovation in bag design—particularly through material engineering and anti-static technology—can address industry-specific challenges. This report analyzes the technical specifications, safety mechanisms, and market relevance of pasted valve bags, supported by case studies and global data.

2. Technical Specifications: Thickness, Weight, and Size

VidePak’s pasted valve bags are tailored to diverse industrial needs. Key parameters include:

2.1 Thickness and Grammage

- Thickness Range: 80–150 microns, optimized for puncture resistance and flexibility.

- Grammage (GSM): 90–120 GSM, balancing tensile strength (1,000–1,500 N/cm²) and material efficiency.

Example: For cement packaging, 120 GSM bags with 140-micron thickness prevent leakage during pneumatic filling, reducing waste by 12% compared to standard bags.

2.2 Size Customization

- Dimensions: Standard sizes range from 50 cm × 80 cm to 70 cm × 110 cm, with custom options for bulkier materials like silica sand.

- Valve Design: Precision-sealed valves (2–4 cm diameter) enable dust-free filling, critical for OSHA-compliant worksites.

3. Anti-Static Mechanisms: Safeguarding Hazardous Environments

Static electricity poses explosion risks in environments with combustible dust. VidePak integrates anti-static properties through:

3.1 Conductive Materials and Faraday Cage Principle

- Material Composition: Polypropylene (PP) woven fabric embedded with carbon fibers or metal-coated threads, achieving surface resistance <10⁶ Ω.

- Faraday Cage Design: Multi-layer laminates (e.g., PP + aluminum foil) shield contents from external electrostatic discharge (ESD), protecting sensitive additives like epoxy resins.

Case Study: A South Korean construction firm reported a 40% reduction in static-related incidents after switching to VidePak’s anti-static valve bags for transporting powdered fire retardants.

3.2 Grounding and Dissipative Coatings

- Integrated Grounding Strips: Copper strips woven into bag seams channel static to ground points during handling.

- Dissipative Liners: Hydrophobic coatings reduce friction-induced static, critical for silica fume packaging.

4. Load Capacity and Durability Testing

VidePak’s bags undergo rigorous testing to ensure performance under stress:

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Static Load Capacity | 20–50 kg (depending on GSM) |

| Dynamic Load Capacity | 10–25 kg (vibration-resistant for transport) |

| Stacking Strength | Up to 8 layers without deformation |

| Temperature Resistance | -30°C to 80°C |

Data Source: VidePak’s internal quality reports (2024) and ISO 21898 certification standards.

5. Market Relevance and Case Studies

5.1 Global Demand and Regulatory Compliance

- The global construction packaging market is projected to grow at 5.8% CAGR (2024–2030), driven by urbanization in Asia-Pacific.

- VidePak’s bags comply with EU Directive 94/62/EC (packaging waste) and NFPA 652 (combustible dust standards).

5.2 Case Study: Cement Logistics in Germany

A German cement manufacturer adopted VidePak’s valve bags for their moisture-resistant liners and anti-static properties. Results included:

- 18% faster filling speeds due to Starlinger’s automated valve sealing.

- Zero static-related downtime over 12 months.

6. FAQs: Addressing Industry Concerns

Q1: How do anti-static bags prevent explosions?

A: Conductive materials and grounding strips dissipate static charges, reducing ignition risks in combustible environments.

Q2: Can these bags withstand high-moisture conditions?

A: Yes. PE-coated liners provide 99% moisture barrier efficiency, ideal for gypsum transport.

Q3: What customization options are available?

A: VidePak offers multi-color printing, UV-resistant coatings, and sizes up to 100 cm × 120 cm. Lead time: 10–15 days.

7. Strategic Innovations and Sustainability

VidePak is pioneering PE-coated valve bags for construction waste recycling, aligning with circular economy goals. Additionally, collaborations with recyclers like TerraCycle ensure 30% post-consumer PP reuse in bag production.

8. Conclusion

Pasted valve bags are more than packaging—they are a safety imperative. VidePak’s fusion of Starlinger’s precision and anti-static innovation positions it as a leader in sustainable, high-performance solutions. As Ray emphasizes, “In an industry where a single spark can cause catastrophe, our bags are engineered to protect lives, products, and the planet.”

For insights into automated packaging advancements, explore our analysis of Starlinger’s self-opening sack systems.

This report integrates data from industry certifications, case studies, and VidePak’s operational metrics to provide actionable insights for stakeholders in construction and packaging.