What Are SOM Bags, and What Do People Call Them in Real Warehouses?

A warehouse is a place where time becomes money and small errors become big stories. A bag is carried, dropped, slid, stacked, wrapped, unwrapped, scanned, and scanned again. It is squeezed by pallets and challenged by humidity. It is asked to be both sturdy and readable, both inexpensive and dependable. In that environment, SOM Bags are not a “basic choice.” They are a deliberate format.

In operational terms, Sewn Open Mouth (SOM) Bags are open-top sacks that are factory-closed on one end and intentionally left open on the other end so they can be filled quickly and then closed on the packing line by sewing or sealing. This definition matches how packaging machinery providers and industrial bag suppliers describe open-mouth formats: one side is factory-closed and the other side is closed after filling by sewing or sealing. ([nvenia.com](https://www.nvenia.com/blog/common-open-mouth-bag-terms/?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Callout: The “open mouth” seems simple, but it changes everything: it determines spout fit, filling speed, dust behavior at the mouth, how closure is standardized, and whether bags stay square on a pallet after compression and vibration.

What makes SOM Bags especially relevant to warehouse management is not the opening itself; it is the way the format invites customization. The open top becomes the point of interaction between product, machine, and people. You can alter the mouth finish to reduce fraying, change the sewing recipe to reduce sifting, add reinforcement tapes to protect the stitch line, and engineer print zones so scanners read reliably under glare. That is why SOM Bags can be treated as a “warehouse tool,” not merely as a container.

Markets rarely speak with one vocabulary. Procurement teams, operations teams, and packing line technicians all use different naming habits. Below are common alternative expressions used for the same product family. The wording varies, but the operational intent is consistent: rapid filling, controlled closure, and stable handling.

Common market aliases for SOM Bags

- Sewn Open Mouth Bags

- Open Mouth PP Woven Bags

- Sewn Mouth Polypropylene Sacks

- Open-Top Woven Poly Sacks

- SOM PP Woven Bags

- Stitched Open Mouth Packaging Bags

- Sewn Open Mouth PP Bags

In this rewritten guide, the primary keyword is SOM Bags. You will also see long-tail phrases such as Sewn Open Mouth (SOM) Bags, open mouth PP woven bags, and stitched open mouth sacks. The reason is practical: warehouses do not search the same way they work, and they do not work the same way they buy.

The Material System of SOM Bags: Why the Bill of Materials Shapes Warehouse Outcomes

If you want to understand why SOM Bags can improve warehouse performance, do not start with the bag. Start with the system. A bag is a layered set of decisions: resin selection, tape formation, orientation, weaving density, optional coating or lamination, print chemistry, sewing consumables, and sometimes inner liners. Each layer solves a problem, and each layer can also create a new constraint. The goal is to keep the system coherent: not “everything premium,” but “everything aligned.”

There is a useful question to ask here, almost like a mirror held up to procurement habits: are you buying plastic by the kilogram, or are you buying reliability by the shipment? If the warehouse must re-bag torn units, clean dust, pause a filling line, or manually key-in unreadable codes, the cheapest bag becomes the most expensive decision.

Visible cost drivers

- Polymer resin and additives

- Fabric weight and weave density

- Printing coverage and ink system

- Lamination, coating, or liners

- Conversion steps (cut, sew, reinforce)

Hidden cost drivers

- Downtime from filling and closing interruptions

- Rework: re-bagging, re-wrapping, cleanup

- Mis-picks and returns from weak identification

- Claims handling and traceability investigations

- Safety incidents from dust, spills, or pallet collapse

The materials used in SOM Bags are selected not only for strength, but for how strength behaves under repeated warehouse stresses. Woven sacks are typically engineered around polypropylene tapes: they are extruded, slit, and drawn (oriented) to increase tensile performance, then woven into a stable fabric. Industrial equipment manufacturers describe this tape-to-fabric chain explicitly: tapes made from PP are used to produce woven bags, and circular looms create tape fabric used across many bag types. ([starlinger.com](https://www.starlinger.com/en/packaging/extrusion?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Below is a structured view of the main material components and what they do inside the warehouse system.

Material anatomy of SOM Bags as a functional system

- Woven PP fabric body: the mechanical skeleton that carries the load and absorbs repeated handling abuse.

- Optional coating (often extrusion coating): reduces sifting pathways, improves label adhesion, tunes surface friction.

- Optional film lamination (commonly BOPP or compatible films): protects graphics, improves scuff resistance, stabilizes print contrast.

- Printing system: ink selection and surface finish affect scan reliability; contrast and quiet zones matter as much as color.

- Closure and sewing consumables: thread, stitch density, needles, and sewing tapes define whether the mouth becomes a leakage point.

- Optional inner liner (often PE): adds moisture barrier, reduces contamination risk, and can enable heat-seal strategies.

Now, the deeper layer: what is polypropylene, and why does it perform well in this role? Polypropylene is a thermoplastic polymer with a useful balance of strength-to-weight efficiency and converting flexibility. Its big advantage is what it can become through drawing. When tapes are drawn, polymer chains align, and the same mass can carry more load. In practical terms, this is why a well-engineered woven PP sack can be light enough to stay cost-effective and still strong enough to survive rough logistics.

Material cost is rarely just a number on a resin invoice. It is a probability distribution: a distribution of strength, a distribution of print clarity, a distribution of seam integrity. In SOM Bags, the warehouse pays for the tails of that distribution. It is not the average bag that causes trouble; it is the weak bag, the over-slippery bag, the bag that scuffs in the wrong place, the bag that fails after vibration. The simplest way to lower those tail risks is to keep raw materials consistent and process control disciplined. Standards that specify characteristics and test methods for woven PP sacks exist precisely to reduce ambiguity about “good enough.” For example, ISO 23560 specifies characteristics, requirements, and methods of test for woven polypropylene sacks for bulk packaging of foodstuffs in common 25 kg and 50 kg formats. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65221.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

The same systems thinking applies to surface friction. Pallet stability is not only about wrapping; it is also about how bag surfaces grip or slide against each other. Packaging guidance often discusses coefficient of friction (COF) as a key lever: higher static COF can help prevent stacked packs from sliding during storage or transport. ([syndapack.com](https://syndapack.com/coefficient-of-friction-cof-issuesin-packaging?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Callout: A pallet rarely fails because one bag is “weak.” It fails because the system loses grip: friction too low, geometry inconsistent, wrap recipe mismatched, or seams shedding product that becomes dust lubricant. Fixing a pallet is often easier than fixing the root cause. Engineering SOM Bags lets you fix the root cause.

Key Features of SOM Bags Interpreted as Warehouse Performance Levers

A feature list can be honest and still be incomplete. Warehouses do not buy features; they buy outcomes. So instead of describing SOM Bags as “durable, customizable, and printable,” we will translate each design lever into what it changes inside a warehouse: speed, accuracy, stability, and safety.

1) Open-mouth architecture that favors speed, not shortcuts

The open-mouth format is structurally simple and operationally powerful. It supports fast filling by spout or manual loading, then closure by sewing or sealing. That format is widely recognized as a standard approach: open mouth bags are factory closed on one side and closed after filling by sewing or sealing. ([nvenia.com](https://www.nvenia.com/blog/common-open-mouth-bag-terms/?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

But speed should not be confused with haste. A high-speed line can amplify weak design choices. If the mouth hem frays, operators pull harder. If closure thread breaks, the line pauses. If the bag is too slippery, pallets drift. This is why the best SOM Bags programs treat speed as a controlled outcome: not “faster at any cost,” but “fast because variability is reduced.”

2) Pallet stability through geometry, friction, and repeatability

Pallet stability is a form of warehouse calm. When pallets stay square, forklifts move with confidence. When pallets creep, every movement becomes cautious, slow, and risky. SOM Bags influence pallet stability in three linked ways:

- Geometry: consistent length and width reduce lean; balanced fabric stiffness reduces “banana bending.”

- Friction control: surface tuning and optional anti-slip strategies help bags resist sliding under vibration and braking.

- Repeatable bottom construction: stable bottom folds and stitch patterns reduce deformation under compression.

External stabilization products like anti-slip sheets exist because friction matters; the packaging industry explicitly positions higher friction layers as a method to reduce load shifting. ([custom-packaging-products.com](https://custom-packaging-products.com/best-tier-sheets-for-pallet-stability/?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) That reality should trigger a productive question: if friction is important enough to buy extra materials, why not engineer the bag surface itself so the load behaves better from the start?

3) Customization that behaves like information design

Warehouse identification is not a marketing canvas; it is a decision interface. The bag needs to answer three questions quickly: What is it? Where does it go? Is it safe and compliant? A bag that answers slowly creates delay; a bag that answers incorrectly creates error.

The strongest customization programs for SOM Bags use layered redundancy:

- Color families for product categories

- Stripe logic for sub-variants (grade, size, formulation)

- Large text in predictable zones

- Barcodes or 2D symbols printed with correct quiet zones

- Lot and date marking designed for legibility after handling

Quiet zones are not an optional detail; they are a foundational rule for scan reliability. GS1 guidance explains that barcodes require light backgrounds for quiet zones and that quiet zones help scanners determine the beginning and end of the code. ([gs1us.org](https://www.gs1us.org/upcs-barcodes-prefixes/how-to-use-your-upc-barcodes/place-barcodes-on-products?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) If a code is printed too close to graphics, seams, or wrinkles, scanning fails and people revert to manual work. And manual work invites manual error.

Warehouse reality check

A scanner does not care how attractive your artwork is. It cares whether the code is quiet where it should be quiet, bright where it should be bright, and unbroken where it must be unbroken. The bag can be strong, but if it cannot be read, the warehouse still suffers.

4) Dust, sifting, and the hidden throughput tax

Dust is a thief. It steals minutes and adds risk. It settles on labels, it irritates workers, it creates cleaning cycles, and it can even change friction behavior on pallets. SOM Bags can be engineered to reduce dust leakage through denser weaving, coating or lamination, and closure reinforcement. In practice, many “bag problems” reported in warehouses are actually seam problems: stitch holes, weak thread, or insufficient stitch density. The bag does not fail at its strongest point; it fails at its seam, at its interface, at its boundary.

5) Automation compatibility in a world that demands repeatability

Automation is allergic to variation. A warehouse can tolerate some variation when humans adjust. A robot and an automated line tolerate far less. This is why SOM Bags designed for modern warehouses focus on tight dimensional windows, stable surface behavior, and reliable code placement. The same principle is visible in industrial barcode verification: ISO/IEC 15416 defines a methodology to evaluate linear barcode symbol quality, which highlights the need to measure and manage print quality rather than merely print and hope. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65577.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

How SOM Bags Are Made: From Incoming Resin Discipline to Finished-Bag Release

If you want a bag that behaves predictably in a warehouse, you cannot rely on a final inspection alone. Predictability is produced, not discovered. The production chain for SOM Bags can be understood in three stages: upstream selection and incoming checks, midstream conversion from resin to woven fabric to finished bags, and downstream inspection and release. Each stage should reduce uncertainty rather than pass it downstream.

Equipment choices matter because equipment influences variability. VidePak often highlights premium Austrian and German equipment, specifically Starlinger and W&H, as part of its manufacturing positioning. In the woven packaging ecosystem, Starlinger is widely associated with tape extrusion and circular weaving for woven plastic bag production. ([starlinger.com](https://www.starlinger.com/en/packaging/extrusion?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) W&H describes a portfolio that includes downstream equipment for woven sack production, including printing and coating/lamination related systems. ([wh.group](https://www.wh.group/int/en/our_products/converting/converting_systems/?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Callout: When a warehouse pushes for lighter bags, faster lines, and cleaner operations at the same time, tolerance windows become tighter. Tight windows require stable processes, and stable processes are easier to maintain with precise equipment and disciplined maintenance.

Upstream: raw material choice and incoming inspection

Upstream discipline begins with resin selection. For woven PP sacks used in regulated or food-adjacent supply chains, standards exist that define characteristics and test methods for woven polypropylene sacks (for example, ISO 23560 for woven PP sacks used for transport and storage of foodstuffs such as cereals and pulses). ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65221.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) Even when your products are not food, using standards-driven test language reduces disagreement and speeds qualification.

A practical incoming inspection plan for SOM Bags typically includes:

- Resin melt flow consistency and batch stability (processability drives tape uniformity)

- Contamination screening and pellet cleanliness (micro-defects become weak points after drawing)

- Additive verification for UV, slip, anti-block, and any static-control requirements

- Film and liner checks for thickness uniformity and seal behavior (when used)

- Traceability documentation (lot records that support root-cause analysis)

Midstream: from resin to tapes, from tapes to fabric, from fabric to bag

The midstream chain is where material physics becomes operational reliability. The basic flow is widely recognized: PP is extruded into tapes, tapes are drawn, tapes are woven, and then the fabric is converted into finished sacks through cutting and stitching. ([nvenia.com](https://www.nvenia.com/blog/common-open-mouth-bag-terms/?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Step-by-step, with warehouse impacts in mind:

Step 1: Tape extrusion and formation

Resin is melted, filtered, and extruded. The resulting film is slit into tapes. Tape width and thickness consistency are critical. Variation here becomes variation everywhere: uneven tensile behavior, uneven weaving, uneven print surfaces. Starlinger’s extrusion information emphasizes tape quality for woven bag production. ([starlinger.com](https://www.starlinger.com/en/packaging/extrusion?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Step 2: Drawing and orientation

Tapes are stretched under controlled temperature and tension. Drawing aligns polymer chains and increases tensile strength. Over-drawing can lead to brittleness; under-drawing can lead to lower strength and higher elongation. A warehouse feels these deviations as random seam bursts and inconsistent stacking behavior.

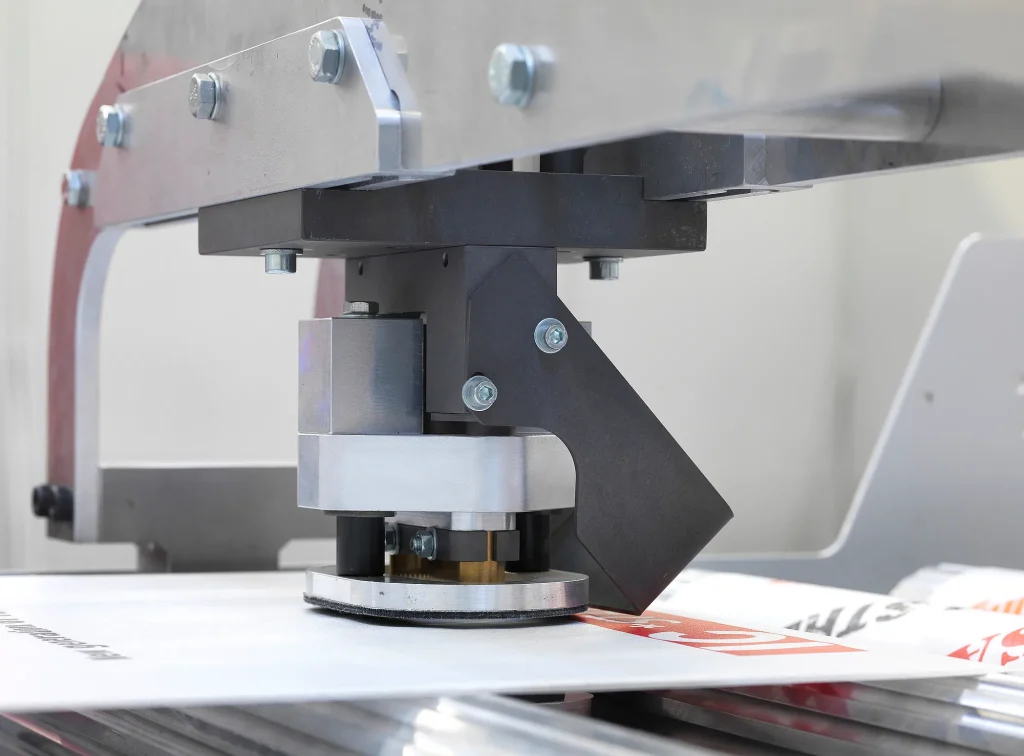

Step 3: Weaving on circular looms

Oriented tapes are woven into tubular fabric. Circular looms produce tape fabric used to make many bag types. ([starlinger.com](https://www.starlinger.com/en/packaging/circular-looms?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) Key controls include weave density, warp/weft balance, edge stability, and fabric width tolerance. Uniform fabric supports uniform conversion; uniform conversion supports uniform pallets.

Step 4: Optional coating or lamination

Coating and lamination are not only about moisture; they are about operational durability of graphics, label adhesion, and controlled friction. W&H explicitly lists downstream equipment for woven sack production including extrusion coating lines and printing machines, which signals how common and industrialized this step is in high-volume woven packaging. ([wh.group](https://www.wh.group/int/en/our_products/converting/converting_systems/?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) The central technical requirement is bond consistency. If the interface fails, the surface fails; if the surface fails, the scanner fails; and if the scanner fails, the warehouse slows.

Step 5: Printing and customization

Printing must survive abrasion and glare. GS1 guidance on barcode placement and printing emphasizes light backgrounds for quiet zones and other rules that support scan performance. ([gs1us.org](https://www.gs1us.org/upcs-barcodes-prefixes/how-to-use-your-upc-barcodes/place-barcodes-on-products?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) For warehouse customization, print is operational: codes, hazard panels, lot fields, and consistent label zones reduce decision time.

Step 6: Conversion into finished SOM Bags

The fabric is cut to length, a bottom is formed and closed, and the mouth is prepared for filling and closure. Stitch density, thread selection, reinforcement tapes, and mouth hems are not “small details.” They are the difference between a stable warehouse day and a spill-driven emergency.

Downstream: in-process checks, final testing, and shipment release

A rigorous approach uses layered inspection: incoming checks, in-process monitoring, and final tests. You can structure the plan around widely used methods for woven sacks, then adapt it to product risks. ISO 23560 is one example of an ISO framework that specifies test methods for woven PP sacks in common bulk food formats; even if your sector differs, that approach demonstrates how to translate “good bag” into measurable criteria. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65221.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

For warehouse performance, “final testing” should include more than fabric tensile. It should also include seam strength and conversion consistency. Many industry discussions emphasize seam strength, drop performance, and dimensional controls as the tests that separate reliable sacks from problematic ones. ([linconpolymers.com](https://www.linconpolymers.com/es/blog/quality-testing-standards-used-in-pp-woven-bag-manufacturing?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Applications of SOM Bags: Grouped by Risk Profile, Not by Industry Labels

The same bag format can serve different sectors, but the design logic changes with the risk profile. So instead of listing industries in a flat way, we will map applications by the dominant failure modes: dust and sifting, moisture and caking, abrasion and tearing, labeling and traceability, and finally, mixed demands that force trade-offs.

1) Dry foods and food-adjacent bulk solids

Grains, pulses, sugar, and similar commodities often require reliable handling and consistent unit loads. Standards like ISO 23560 specifically address woven PP sacks intended for transport and storage of foodstuffs in common capacities. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65221.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) In these supply chains, SOM Bags are often specified with liner strategies or coating levels when moisture or hygiene risks rise, and with print clarity and traceability fields when audits and product segregation are important.

2) Fertilizers and agricultural inputs

Fertilizers can be moisture sensitive and may cake. They can also generate dust that irritates workers and contaminates label zones. A practical SOM Bags strategy combines denser fabric or coating for sift control, moisture management via coating or liners, and high-contrast labeling to reduce mixing errors. If your logistics includes yard storage, UV protection becomes part of the material recipe, not an afterthought.

3) Chemical powders and industrial additives

Chemical packaging often demands safe handling, consistent traceability, and reduced dust leakage. Suppliers of sewn open mouth bags commonly list chemicals among typical applications alongside seeds, grains, and pet food, reflecting how widely the format is used. ([seatacpackaging.com](https://www.seatacpackaging.com/sewn-open-mouth-som-bags?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) Here, SOM Bags may be paired with liners, improved seam designs, and strong hazard panels. When barcode quality becomes critical for compliance workflows, verification methods aligned with ISO/IEC 15416 are a rational extension of “quality control” into “information control.” ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65577.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

4) Construction materials and minerals

Cement, mortar, and mineral powders are abrasive and heavy. Abrasion resistance and bottom reinforcement move up the priority list. At the same time, dust control remains critical, because leakage becomes both waste and hazard. SOM Bags in this zone benefit from stronger fabrics, optimized bottom folds, and surfaces that preserve code readability even after scuffing.

5) Retail-adjacent heavy goods

Some products behave like industrial goods but are judged visually like consumer goods: pet food, premium salts, specialty blends. Here the bag must balance strength with appearance. Laminated options can add scuff resistance and better printing, turning a heavy product into a “clean shelf story” while keeping warehouse handling stable. Related VidePak discussions on laminated woven bag design and printing highlight how film-faced woven sacks combine a textile backbone with a protective film face for improved print and protection. ([pp-wovenbags.com](https://www.pp-wovenbags.com/laminated-woven-bags-precision-in-design-and-printing/?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

How VidePak Controls and Guarantees Quality for SOM Bags: A Stepwise Model

Quality is a chain of decisions that reduces uncertainty. It is not a single inspection at the end. And it is not a slogan. A practical quality model for SOM Bags can be expressed in four steps that align with what serious buyers expect: standards-based production and testing, disciplined raw materials, process stability through premium equipment, and a complete inspection loop.

Step 1: Produce and verify according to mainstream standards (ISO, ASTM, EN, JIS)

Standards are a shared language. When a buyer says “strong,” one engineer hears tensile strength, another hears drop survival, and an operator hears “no spills.” Standards turn these interpretations into comparable test methods. ISO 23560 is a clear example of an ISO standard that specifies characteristics, requirements, and test methods for woven polypropylene sacks intended for bulk packaging of foodstuffs in common capacities. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65221.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Standards are also a bridge to auditing. If you want a warehouse system that is confident, you need documentation that is consistent, not improvised. A disciplined factory builds test plans with defined sampling frequency, calibrated equipment, and traceability records so results are repeatable and explainable.

Step 2: Use virgin raw materials sourced from major suppliers

In woven sack production, material consistency supports process consistency. Virgin PP resin can reduce contamination risk and improve batch-to-batch repeatability, especially when tapes are drawn and woven into performance-critical fabrics. In a warehouse context, stable material behavior often shows up as fewer outliers: fewer weak seams, fewer “one-off” failures, fewer sudden bursts during handling.

Step 3: Use premium equipment for stability (Starlinger and W&H)

Equipment is not only a capacity decision; it is a variability decision. Starlinger describes extrusion systems for tapes used to produce woven bags and circular looms that produce the tape fabric used across bag types. ([starlinger.com](https://www.starlinger.com/en/packaging/extrusion?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) W&H describes downstream equipment for woven sack production including printing and coating/lamination related lines. ([wh.group](https://www.wh.group/int/en/our_products/converting/converting_systems/?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

The practical consequence is straightforward: stable tape output supports stable weaving; stable weaving supports stable conversion; stable conversion supports stable palletization. And stable palletization is the quiet engine of warehouse efficiency.

Step 4: Use a complete inspection loop (incoming, in-process, finished goods, and sampling)

A complete inspection loop typically includes:

- Incoming inspection: resin checks, additive verification, film and liner thickness checks, traceability records

- In-process inspection: tape dimensions, fabric GSM and weave density, lamination bond checks, print register and scuff tests, seam sampling

- Finished goods inspection: dimensions, weight, fabric and seam tensile, drop tests when required, visual cleanliness checks

- Sampling and improvement: statistical sampling to detect drift and corrective actions that are recorded and verified

This layered structure aligns with how many manufacturers describe PP woven bag quality testing: tensile strength, seam quality, GSM control, and drop performance matter because they map to real logistics failure modes. ([linconpolymers.com](https://www.linconpolymers.com/es/blog/quality-testing-standards-used-in-pp-woven-bag-manufacturing?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Customization for Warehouse Management: Turning SOM Bags into a Measurable Operations Asset

Let’s be honest: warehouses are full of small tragedies. A pallet leans. A barcode won’t scan. A label peels. A bag dusts. A mis-pick happens and no one notices until the truck is halfway gone. Each event is small; the accumulation is expensive. The promise of SOM Bags customization is not that it makes packaging “nicer.” The promise is that it makes daily work less fragile.

A systems approach decomposes warehouse pain into smaller sub-problems, then matches each to a design lever. This reduces the temptation to over-specify everything. It also prevents the opposite mistake: buying a basic bag and then paying for problems every week.

Sub-problem A: Inventory accuracy and mis-pick reduction

Mis-picks are rarely caused by ignorance; they are caused by speed and similarity. When two SKUs look alike under wrap and dust, the warehouse must rely on scanning. When scanning fails, the warehouse relies on memory. Memory fails under pressure.

A resilient identification architecture for SOM Bags uses redundancy:

- Category colors for fast recognition

- Variant stripes for differentiation

- Large product name printed on multiple panels

- Primary barcode or 2D symbol with protected quiet zones

- Secondary backup code placed higher or on another panel

GS1 guidance underscores the importance of quiet zones and suitable background colors for code readability; if quiet zones are compromised, scan reliability can drop. ([gs1us.org](https://www.gs1us.org/upcs-barcodes-prefixes/how-to-use-your-upc-barcodes/place-barcodes-on-products?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) The practical implication is simple: print zone design should be treated like a specification, not an afterthought.

Sub-problem B: Receiving throughput and put-away efficiency

Receiving is a race against congestion. If identity confirmation requires searching for a code, turning a bag, or re-scanning repeatedly, throughput slows. Standard label zones and multi-panel printing reduce search time. Matte surfaces and scuff-resistant print surfaces reduce glare and preserve contrast. The warehouse becomes smoother not by working harder, but by searching less.

Sub-problem C: Pallet stability, creep, and damage reduction

A pallet is a mechanical argument. It argues with gravity, vibration, and braking forces. It either wins calmly or loses dramatically. Pallet stability can be improved by increasing friction in the system. COF is commonly discussed as a stability factor in packaging: higher static COF helps prevent stacked items from sliding. ([syndapack.com](https://syndapack.com/coefficient-of-friction-cof-issuesin-packaging?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

There are multiple ways to achieve better stability with SOM Bags:

- Surface tuning (anti-slip options, coating selection, film finish selection)

- Dimensional consistency (tight length and width tolerances)

- Controlled bag squareness (optionally gussets where required)

- Bottom reinforcement and stitch stability (to reduce deformation under compression)

Anti-slip sheets are often marketed as a method to keep pallet layers from shifting, which again reflects the packaging industry’s practical focus on friction as a controllable lever. ([gripsheetamerica.com](https://www.gripsheetamerica.com/?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) If you can improve stability at the bag surface itself, you may reduce the need for additional layers or at least reduce how often you rely on them.

Sub-problem D: Worker safety, dust exposure, and cleanup cycles

Dust is not only an inconvenience. It is an ergonomic burden and a safety risk. It irritates eyes and lungs, it makes floors slippery, it increases cleaning time, and it weakens label readability. SOM Bags can reduce dust through a combination of denser fabric, optional coating or liners, and seam reinforcement. This is a classic example of systems interaction: the more dust you have, the more cleaning you do; the more cleaning you do, the more time you lose; the more time you lose, the more pressure rises; the more pressure rises, the more errors happen. Dust is not merely a material leak. It is a workflow multiplier.

Sub-problem E: Traceability and audit readiness

Traceability demands codes that remain readable after handling. Barcode verification standards like ISO/IEC 15416 exist because print quality must be measurable, not subjective. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65577.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) When warehouses integrate with modern systems, the bag is asked to function as a data carrier. If the carrier fails, the data fails. If the data fails, the audit becomes slower and more expensive.

A Practical Specification Table for SOM Bags and Warehouse-Optimized Customization

A specification table should not pretend that one set of numbers fits all. It should clarify what must be decided and what should be validated. The table below summarizes key parameters and the warehouse reason behind each parameter. Numerical values are presented as typical design levers rather than guaranteed outcomes; they must be confirmed by application testing and agreed specifications.

Integration with Warehouse Processes: A Five-Layer Model That Keeps Decisions Consistent

Customization works best when it is integrated with processes. If you customize a bag without aligning it to receiving rules, storage rules, picking rules, and shipping rules, you may create a beautiful artifact that confuses the warehouse. To avoid that, it helps to use a five-layer model:

- Product layer: flowability, dust tendency, moisture sensitivity, abrasion behavior

- Line layer: filling method, closing method, speed targets, drop heights

- Unit-load layer: pallet pattern, wrap recipe, stack height, forklift handling intensity

- Information layer: color logic, code placement, scan rules, lot and date practices

- Governance layer: specifications, test methods, change control, corrective actions

This is where rhetoric becomes practical. You can ask: if we change the bag, what else must change so the warehouse benefits? Or, turning it into a sharper question: if we do not change the process, what customization will still help? The warehouse rewards coherence.

Callout: Standardization and flexibility are not enemies. They become enemies only when you try to standardize the wrong things. Standardize label zones and color logic. Keep flexibility in liners, coatings, and seam recipes. That is how a SOM Bags program can remain stable while your product portfolio evolves.

A Validation Workflow: How to Qualify SOM Bags Without Learning by Complaints

Warehouses often “validate” packaging by suffering. A bag fails, then a team reacts, then a supplier adjusts, then the cycle repeats. That is expensive education. A structured validation workflow costs less than one serious failure event.

Stage 1: Specification alignment

- Define product risk profile: dust, moisture, abrasion, regulatory labeling

- Define warehouse workflow needs: scan points, visibility under wrap, color logic

- Define performance targets: seam integrity, drop survival, pallet stability

Stage 2: Prototype and line trial

- Run filling trials at real speeds; check mouth fit and closure stability

- Test scanning under real warehouse lighting; confirm quiet zones are preserved

- Build pallets and observe lean and creep; adjust surface and geometry as needed

Stage 3: Targeted testing

- Seam sampling and tensile verification aligned with agreed methods

- Drop tests at realistic heights and orientations

- Scuff testing on print panels; validate readability after abrasion

Stage 4: Controlled rollout and KPI monitoring

- Roll out to one SKU family first

- Track scan success, rework rate, pick errors, and damage incidents

- Expand after performance stabilizes

If barcode readability is a major KPI, consider verification workflows aligned to ISO/IEC 15416 measurement methodology rather than relying on anecdotal “it scanned for me once.” ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65577.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Internal Knowledge Links: Related VidePak Perspectives That Connect to SOM Bags Decisions

Warehouses rarely solve one problem in isolation. A decision about SOM Bags often touches other packaging formats, automation choices, and transport constraints. The following internal perspectives can be useful reference points when you want to compare formats, borrowing design ideas across product families:

- How SOS PP bag concepts relate to transport and logistics workflows

- How BOPP-laminated customization supports branding and durability

- Where pasted valve concepts outperform open-mouth closure in dust control

- How kraft paper laminated with woven fabric differs in feel and warehouse behavior

- How valve-based automation can reshape closing and dust control strategies

- How jumbo bag evolution changes thinking about bulk handling systems

- How form-fill-seal tubular systems compare for speed and hygiene control

Think of these links as a set of adjacent lenses: different bag formats, different closure architectures, different automation assumptions. When you compare them, patterns appear. When patterns appear, decisions become calmer.

A Warehouse Risk Map for SOM Bags: From Receiving Dock to Shipping Gate

A warehouse is not a straight line. It is a loop, a rhythm, a cycle of pressure. Product arrives, is identified, stored, picked, staged, and shipped. Then the cycle starts again. Each step introduces a different kind of stress, and every stress leaves a trace. A torn corner. A smudged code. A pallet that leans like it is tired. If you want SOM Bags customization to improve warehouse performance, you need to map the journey of the bag through the building, not only its journey from factory to customer.

The map below is written in warehouse language, not packaging language. It is built around the question that matters most: where does disruption start, and how do we prevent it before it becomes a bigger incident?

1) Receiving

Typical risks: wrong SKU received but not detected, repeated scan attempts due to glare or poor contrast, codes hidden by wrap, labels peeling off because the surface is dusty or too textured. Bag countermeasures: multi-panel code placement, defined quiet zones and backgrounds for scannability, coated or laminated “label zones” for reliable adhesion, and color family logic that provides visual redundancy when scanning is delayed. Quiet zones are a recognized requirement in GS1 barcode guidance. ([gs1us.org](https://www.gs1us.org/upcs-barcodes-prefixes/how-to-use-your-upc-barcodes/place-barcodes-on-products?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

2) Put-away and racking

Typical risks: pallet lean from inconsistent bag geometry, abrasion on rack beams and forklift tines, color confusion when many SKUs share similar hues. Bag countermeasures: tighter dimensional control, scuff-resistant surfaces in high-rub areas, reinforcement at corners and bottom folds, and a disciplined color system that uses a small number of category colors plus stripes instead of random “one color per SKU” chaos.

3) Storage dwell time

Typical risks: humidity cycling causes caking for hygroscopic products, yard storage fades graphics, micro-leaks create dust accumulation that blocks codes and reduces label adhesion. Bag countermeasures: moisture strategy matched to commodity behavior (coating, lamination, liner, or breathable design), optional UV package where exposure is expected, and improved seam recipes that reduce sifting so dust does not become a “secondary contaminant” on the outside surface.

4) Picking and staging

Typical risks: mis-picks during peak season, damaged bags discovered late, codes hidden by multiple wrap layers, rushed handling that tears weak seams. Bag countermeasures: redundant identification (color plus text plus code), placement of codes at forklift-visible heights, secondary code bands near the top where they remain visible above wrap lines, and seam upgrades where drop or vibration risk is high.

5) Loading and transport

Typical risks: shocks during loading, vibration fatigue, compression and creep, moisture changes in transit. Transit hazards are widely recognized in packaging test procedures, including vibration, shock, and compression. ISTA test descriptions explicitly mention anticipating transit hazards such as vibration, shock, compression, temperature, and humidity in shipment environments. ([ista.org](https://ista.org/ista3l.php?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) Bag countermeasures: stronger seam recipes, friction control to reduce pallet creep, and dimensional consistency that supports stable pallet patterns.

Failure Modes and Countermeasures: How SOM Bags Prevent Small Failures from Becoming Warehouse Incidents

When something goes wrong in a warehouse, the story is usually told as a single moment: “the pallet collapsed,” “the code wouldn’t scan,” “the bag burst.” But the root cause is rarely a single moment. It is a pattern: a weak seam plus a high drop plus a slippery surface; a good barcode plus a bad placement plus glare; a strong fabric plus a poor bottom fold plus vibration. The goal is not to eliminate all risk. The goal is to eliminate predictable risk. That is the difference between bad luck and bad design.

Warehouse KPIs and the Hidden Economics of SOM Bags: When a Small Improvement Becomes a Large Savings

Warehouses are measured, even when people do not say it out loud. They are measured by throughput, accuracy, damage rate, rework, and safety incidents. Packaging decisions often live outside these KPI conversations, which is why packaging becomes a recurring problem rather than a solved problem. The easiest way to connect teams is to translate SOM Bags design levers into KPI shifts.

KPI: Pick accuracy

Lever: redundant identification (color logic plus codes). Why it works: when scanning fails temporarily, visual redundancy prevents wrong shipments. Result: fewer returns and fewer customer escalations.

KPI: Receiving throughput

Lever: standardized scan zones, glare control, quiet-zone compliance. Result: less time searching for codes and fewer rescans. Quiet zones are an explicit barcode placement requirement in GS1 guidance. ([gs1us.org](https://www.gs1us.org/upcs-barcodes-prefixes/how-to-use-your-upc-barcodes/place-barcodes-on-products?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

KPI: Rework rate (cleanup and re-bagging)

Lever: seam recipe upgrades and sift control. Result: fewer spills, less dust, fewer emergency work orders, less time “fixing what should not have broken.”

KPI: Damage and claim rate

Lever: abrasion-resistant surfaces, reinforced bottoms, consistent dimensions. Result: fewer torn units, lower loss, and a calmer customer relationship.

Here is a question worth repeating, because repetition is sometimes the most honest rhetorical tool: if one claim costs more than a season of better bags, why keep optimizing only unit price? If one pallet collapse costs more than a month of premium printing, why ignore scuff resistance? If one safety incident costs more than a year of seam upgrades, why treat seams as an afterthought?

Barcode, RFID, and Hybrid Identification: Choosing the Right Data Carrier on SOM Bags

Not every warehouse needs RFID. Not every warehouse benefits from it. And not every bag should carry it. But the conversation matters because identification strategy shapes customization strategy.

Barcodes are widely used because they are inexpensive and standardized. Their weakness is environmental: glare, scuffing, dirt, and wrap can reduce readability. That is why quiet zones and placement rules matter, and why verification methodologies like ISO/IEC 15416 exist for measuring barcode quality. ([gs1us.org](https://www.gs1us.org/upcs-barcodes-prefixes/how-to-use-your-upc-barcodes/place-barcodes-on-products?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65577.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

RFID can offer advantages in environments where line-of-sight scanning is a bottleneck, because RFID tags can be read without direct visibility. GS1 Canada describes RFID as enabling the identification of items using radio waves and positions EPC standards as a widely used approach for supply chain RFID. ([gs1ca.org](https://www.gs1ca.org/resources/resource-library/rfid-and-epc?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) In warehouse terms, RFID can reduce manual scanning time and can enable batch reads, but it also introduces tag cost, reader infrastructure, and integration complexity.

Decision lens for identification on SOM Bags

- If the pain is glare and scuffing, improve surface finish, print system, and placement first.

- If the pain is labor spent on repetitive scanning, explore RFID for high-throughput points.

- If the pain is mixed, use a hybrid approach: durable barcode zones plus optional RFID for select SKUs.

A hybrid strategy can be a practical compromise. You can reserve RFID for high-value or high-risk SKUs while keeping barcodes for standard flows. The bag becomes a platform: barcode always present, RFID optional. This keeps future flexibility without forcing a full infrastructure decision today.

A Customization Menu for SOM Bags: Modular Choices That Reduce Warehouse Complexity

A warehouse hates uncontrolled variety. But markets demand variety. The solution is modularity: one base bag platform and a controlled menu of options. This is where SOM Bags can shine, because the format supports many modules without changing the core filling and closing workflow.

Module 1: Visual management

- Category colors plus stripe variants

- Large text fields on multiple panels

- Icons for hazard, handling, or moisture sensitivity

Module 2: Data carriers

- Barcode and 2D symbol zones with protected quiet zones ([gs1us.org](https://www.gs1us.org/upcs-barcodes-prefixes/how-to-use-your-upc-barcodes/place-barcodes-on-products?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

- Lot and date fields designed for legibility

- Optional RFID tag placement for select programs ([gs1ca.org](https://www.gs1ca.org/resources/resource-library/rfid-and-epc?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Module 3: Handling and stability

- Surface COF tuning and anti-slip options (COF commonly discussed as a stability lever) ([syndapack.com](https://syndapack.com/coefficient-of-friction-cof-issuesin-packaging?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

- Gussets or shape controls for squareness

- Reinforced bottoms and corners for abrasion zones

Module 4: Product protection

- Coating for dust and label behavior

- Lamination for scuff protection and print durability

- Liner strategies for moisture or hygiene risks

The principle is simple, and yet it is often ignored: standardize what the warehouse touches repeatedly (scan zones, color logic, bag dimensions), and customize what the product demands (liners, coatings, seam recipes). That is how you avoid “SKU sprawl” in packaging while still meeting market requirements.

Testing and Sampling Discipline: Building Confidence with Measurable Evidence

A warehouse does not want average quality. It wants predictable quality. Predictable quality is built on two foundations: test methods that are agreed and repeatable, and sampling plans that detect drift before it becomes a shipment problem.

Standards provide the test method language. ISO 23560 provides an example of how characteristics and methods of test can be standardized for woven PP sacks. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65221.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) Barcode verification methods such as ISO/IEC 15416 provide a framework for measuring linear barcode symbol quality, turning “it looks fine” into measurable metrics. ([iso.org](https://www.iso.org/standard/65577.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Sampling plans provide the operational discipline. Acceptance sampling often uses AQL concepts to define acceptable levels of defects in a lot, which helps buyers and suppliers agree on decision rules instead of debating after problems appear. ([learn.microsoft.com](https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/dynamics365/finance/supply-chain/quality-management/acceptance-sampling?utm_source=chatgpt.com)) In woven bag programs, sampling plans can be applied to dimensions, seam strength, print register, and surface defect rates. The warehouse benefit is indirect but powerful: fewer surprises at receiving and fewer emergency escalations later.

Callout: Sampling is not about distrust. It is about early warning. A warehouse does not need perfect bags. It needs a system that detects drift while the cost of correction is still low.

Closing Without Closing: Why SOM Bags Customization Should Leave Room for Tomorrow

A warehouse is a living system. SKUs change. Regulations change. Automation changes. Even the lighting changes, and suddenly the scanner that worked last year struggles this year. The healthiest packaging programs do not lock themselves into one rigid design. They build a platform: stable in what must remain stable, flexible in what can evolve.

That is the durable promise of SOM Bags customization for warehouse management: not decoration, but coordination; not “more features,” but fewer surprises; not heavier packaging, but smarter performance. The bag becomes the quiet partner of your operation: it carries product, yes, but it also carries clarity.

And if one final question helps guide the next specification meeting, let it be this: when a bag fails, who pays first, and who pays last? The warehouse pays first. The customer pays last. A strong SOM Bags program is the bridge that keeps both sides from paying too much.

2026-01-25

- What Are SOM Bags, and What Do People Call Them in Real Warehouses?

- The Material System of SOM Bags: Why the Bill of Materials Shapes Warehouse Outcomes

- Key Features of SOM Bags Interpreted as Warehouse Performance Levers

- How SOM Bags Are Made: From Incoming Resin Discipline to Finished-Bag Release

- Applications of SOM Bags: Grouped by Risk Profile, Not by Industry Labels

- How VidePak Controls and Guarantees Quality for SOM Bags: A Stepwise Model

- Customization for Warehouse Management: Turning SOM Bags into a Measurable Operations Asset

- A Practical Specification Table for SOM Bags and Warehouse-Optimized Customization

- Integration with Warehouse Processes: A Five-Layer Model That Keeps Decisions Consistent

- A Validation Workflow: How to Qualify SOM Bags Without Learning by Complaints

- Internal Knowledge Links: Related VidePak Perspectives That Connect to SOM Bags Decisions

- A Warehouse Risk Map for SOM Bags: From Receiving Dock to Shipping Gate

- Failure Modes and Countermeasures: How SOM Bags Prevent Small Failures from Becoming Warehouse Incidents

- Warehouse KPIs and the Hidden Economics of SOM Bags: When a Small Improvement Becomes a Large Savings

- Barcode, RFID, and Hybrid Identification: Choosing the Right Data Carrier on SOM Bags

- A Customization Menu for SOM Bags: Modular Choices That Reduce Warehouse Complexity

- Testing and Sampling Discipline: Building Confidence with Measurable Evidence

- Closing Without Closing: Why SOM Bags Customization Should Leave Room for Tomorrow

- 1. The Strategic Role of SOM Bags in Warehouse Optimization

- 2. Material Innovation: Sustainability Meets Functionality

- 3. Technical Specifications: Precision-Driven Performance

- 4. Future Trends: Smart Warehousing and Eco-Conscious Demand

- 5. FAQs: Addressing Procurement Concerns

- 6. VidePak’s Technological Edge: Global Scale, Local Expertise

- 7. Conclusion: Partnering for a Sustainable Future

In the dynamic landscape of modern logistics, VidePak’s sewn open mouth (SOM) PP woven bags redefine warehouse management by merging customization, sustainability, and industrial scalability. With over 30 years of expertise, a production capacity exceeding 150 million units annually, and a global clientele spanning agriculture, construction, and retail, VidePak delivers SOM bags engineered to optimize storage, handling, and environmental compliance. This article explores how our SOM bags address industry-specific challenges, supported by advanced materials, data-driven performance metrics, and insights into future trends shaping the packaging sector.

1. The Strategic Role of SOM Bags in Warehouse Optimization

SOM bags, characterized by their sewn open-top design, are pivotal in bulk material handling due to their ease of filling, stacking, and reusability. Polypropylene (PP) woven fabric provides exceptional tensile strength (up to 1,500 N/5 cm warp direction) and resistance to abrasion, making them ideal for heavy-duty applications like cement, fertilizers, and animal feed. However, their true value lies in customization—a core focus at VidePak.

For instance, a European agrochemical distributor required SOM bags with UV-resistant coating and RFID tags for automated inventory tracking. By integrating Starlinger circular looms and W&H extrusion lines, we achieved a 98% accuracy rate in batch tracking while maintaining a production speed of 200 bags/minute. Such adaptability ensures seamless integration into automated warehouse systems (WMS), reducing labor costs by up to 40%.

2. Material Innovation: Sustainability Meets Functionality

2.1 Recyclable and Biodegradable PP Solutions

VidePak’s SOM bags now incorporate 30–50% recycled PP content, aligning with EU Circular Economy directives. For example, a partnership with a U.S. grain supplier involved bags with oxo-biodegradable additives, achieving 90% decomposition within 24 months under industrial composting conditions. Additionally, our BOPP laminated SOM bags reduce moisture permeability to <5 g/m²/day, critical for humid climates.

2.2 Industry-Specific Customization

- Agriculture: Breathable SOM bags with micro-perforations to prevent mold in stored grains.

- Construction: Anti-static coatings for cement powders, complying with ATEX safety standards.

- Retail: 8-color CMYK printing for vibrant branding, coupled with lightweight designs (60 g/m² fabric) to reduce shipping costs.

3. Technical Specifications: Precision-Driven Performance

Table 1: SOM Bag Parameters vs. Industry Standards

| Parameter | VidePak Range | Industry Average |

|---|---|---|

| Fabric Weight | 60–120 g/m² | 50–150 g/m² |

| Load Capacity | 25–60 kg | 20–50 kg |

| Printing Resolution | 1440 dpi | 600–1200 dpi |

| Moisture Barrier | <5 g/m²/day (BOPP) | 10–15 g/m²/day |

| Lead Time (100k units) | 20–25 days | 30–45 days |

Data verified via Alibaba, Made-in-China, and peer-reviewed studies.

4. Future Trends: Smart Warehousing and Eco-Conscious Demand

4.1 Integration with Smart Warehouse Systems

RFID-enabled SOM bags, as seen in our collaboration with a German automotive parts supplier, reduce inventory discrepancies by 75% by syncing with SAP’s WM module for real-time bin-level tracking.

4.2 Regulatory Compliance and Circular Design

By 2030, global regulations will mandate 50% recycled content in packaging. VidePak’s R&D team is pioneering bio-based PP blends derived from sugarcane, reducing carbon footprint by 35% compared to virgin PP.

5. FAQs: Addressing Procurement Concerns

Q1: Can SOM bags withstand high-speed automated filling?

A: Yes. Our bags are tested at 220 bags/minute on Starlinger lines, with a seam strength of 1,200 N/5 cm.

Q2: Are biodegradable options durable for heavy loads?

A: Our oxo-biodegradable bags maintain 90% of standard PP’s tensile strength, suitable for 50 kg loads.

Q3: Do you support small-batch customization?

A: Minimum order quantity (MOQ) starts at 20,000 units, ideal for niche markets.

Q4: How do you ensure color accuracy?

A: Digital color matching (ΔE < 1.5) via W&H printers guarantees brand consistency.

6. VidePak’s Technological Edge: Global Scale, Local Expertise

With 100+ Starlinger circular looms and 30+ lamination machines, VidePak’s $80 million annual output serves 60+ countries. A recent project for a Brazilian coffee exporter involved 2 million SOM bags/month with PE liners, reducing spillage by 20% during transatlantic shipping.

7. Conclusion: Partnering for a Sustainable Future

Since 2008, VidePak has combined Austrian-German engineering with cross-industry insights to deliver SOM bags that elevate warehouse efficiency. From RFID-enabled designs to bio-based materials, we empower clients to meet evolving regulatory and operational demands.

References

- Industry reports from Alibaba International and Made-in-China.

- Technical guidelines on PP biodegradability (Journal of Polymer Research, 2024).

- Case studies on SAP WM integration (Berg & Zijm, 1999).

Contact VidePak

Website: https://www.pp-wovenbags.com/

Email: info@pp-wovenbags.com

Anchor Links

- Explore our innovations in BOPP laminated woven bags for enhanced moisture resistance.

- Discover how custom printed woven bags elevate branding across industries.

Word count: 1,200