- What Are Industrial Packaging Bags?

- Why Industrial Packaging Bags Matter: A Question of Physics, Safety, and Cost

- Systems Thinking: Decomposing the Industrial Packaging Bags Problem

- Materials and Constructions Used in Industrial Packaging Bags

- Manufacturing Workflows Across Bag Types

- Performance Metrics: How Industrial Packaging Bags Earn Their Keep

- Use Cases: Where Industrial Packaging Bags Prove Themselves

- Problem → Solution → Result: Three Industrial Scenarios

- Horizontal Thinking: Where Disciplines Meet Inside Industrial Packaging Bags

- Vertical Thinking: From Molecule to Pallet, Cause to Effect

- Testing, Standards, and What to Put in the Spec Sheet

- Safety and Electrostatics: When Powders Behave Like Storm Clouds

- Sustainability and End‑of‑Life: Credible Claims for Industrial Packaging Bags

- Implementation Playbook: From RFQ to First‑Pass Yield on Industrial Packaging Bags

- Frequently Asked Questions About Industrial Packaging Bags

- Introduction: Defining Industrial Packaging Bags

- Problem Orientation: What Pain Points Do Industrial Packaging Bags Solve?

- Method: Building a Specification for Industrial Packaging Bags

- Result: Line Throughput, Logistics Stability, and Cleaner Arrivals

- Discussion: Why the Method Works for Industrial Packaging Bags

- System Decomposition: Sub‑Problems Inside Industrial Packaging Bags

- Horizontal Thinking: Cross‑Domain Links That Improve Outcomes

- Vertical Thinking: From Polymer Chain to Pallet Pattern

- Customization: Dimensions, Structures, and Artwork for Industrial Packaging Bags

- Operations: Throughput and Stability Without Guesswork

- Sustainability and End‑of‑Life: Credible, Verifiable Paths

- Implementation: From RFQ to First‑Pass Yield on Industrial Packaging Bags

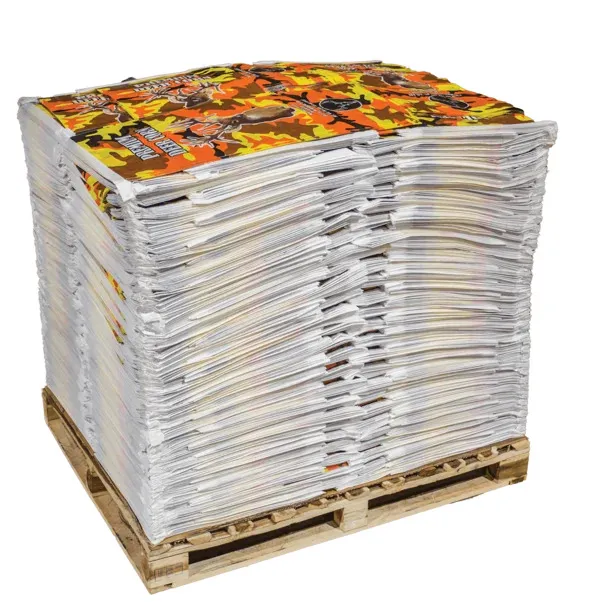

- Ordering and Scale‑Up: Turning Specs Into Supply

- References

What Are Industrial Packaging Bags?

Definition. Industrial Packaging Bags are engineered sacks designed to contain, protect, identify, and transport bulk solids or semi‑solids through demanding supply chains. They typically handle unit loads from a few kilograms up to ton‑level formats. Built for factories, warehouses, ports, and construction sites—not boutique shelves—they prioritize mechanical strength, dust control, safe handling, and repeatable line performance.

In different industries, Industrial Packaging Bags may be referred to as industrial woven bags, bulk sacks, raffia PP sacks, heavy‑duty PE bags, multiwall paper sacks, FIBCs/Jumbo bags, or bulk bags. The labels vary with material and capacity, but the purpose stays constant: secure containment under real‑world stress.

The core attributes of Industrial Packaging Bags include high tensile and tear resistance relative to mass; puncture toughness against sharp granules and pallet corners; moisture control via coatings or liners; stack stability on pallets; printability for codes, warnings, and branding; and compatibility with common handling equipment (baggers, form‑fill‑seal lines, palletizers, forklifts). In many designs, mono‑polyolefin construction supports easier recycling in regions with PP/PE streams.

The typical process for Industrial Packaging Bags follows a disciplined chain: resin selection and compounding; tape extrusion and orientation (for woven PP); weaving on circular or flat looms; surface preparation (corona/primers); coating or lamination (e.g., PP or PE coatings, BOPP films); printing (reverse gravure or high‑definition CI‑flexo); conversion (cutting, gusseting, sewing or heat‑sealing); addition of liners or spouts where required; and quality checks (dimensions, seams, bond strength, COF, rub life). For film‑based bags, blown or cast film extrusion replaces weaving, followed by printing and sealing on FFS or pouch lines. For paper sacks, kraft plies are tubed, valve‑formed, and often PE‑coated or film‑laminated.

Typical applications for Industrial Packaging Bags include chemicals (powders, pellets, additives), fertilizers and soil amendments, cement and mineral fillers, salt and sugar, grains and seeds, resins and masterbatch, animal nutrition, and food‑aid logistics. In ton‑level formats, Industrial Packaging Bags in the form of FIBCs/Jumbo bags move construction materials, agricultural commodities, mining products, and food ingredients with forkliftable efficiency. To explore PP‑woven variants widely used in industry, visit this anchor: Industrial Packaging Bags.

Why Industrial Packaging Bags Matter: A Question of Physics, Safety, and Cost

Supply chains punish weak packaging. Forklift tines bump corners, conveyors abrade faces, tropical humidity wicks through seams, and clamp trucks squeeze stacks. Industrial Packaging Bags survive these insults while keeping products clean, labeled, and measurable. The value is pragmatic: fewer micro‑stops on the bagging line, fewer spills in transit, fewer rejected loads on arrival. In other words: time saved, waste avoided, credibility earned.

A rhetorical question for every plant manager: if the bag tears, who pays—the packaging budget or the production schedule? With Industrial Packaging Bags, the correct answer is “neither,” because the right specification eliminates the failure before it happens.

Systems Thinking: Decomposing the Industrial Packaging Bags Problem

Treat the bag as a system. Decompose, diagnose, and then recombine.

Containment physics. Determine required tensile, tear, puncture, and seam strength based on density and handling. Woven PP fabric GSM, mesh (e.g., 10×10 to 14×14), tape denier, and coating mass govern survivability; film‑based structures rely on film gauge, modulus, and seal integrity. Add liners where dust or aroma control matters.

Filling & line behavior. Target panel‑wise friction windows so Industrial Packaging Bags glide through formers yet grip on pallets (e.g., face COF ≈ 0.25–0.35; back COF ≈ 0.45–0.60). Define mouth formats—open mouth, valve, or spout—for your filler style and speed.

Graphics & traceability. Reverse printing under BOPP or protected print windows keep hazard legends, barcodes, and QR codes scannable after transit. Color governance via Pantone/LAB/RAL prevents drift across suppliers and presses.

Environment & route. For outdoor yards and long sea routes, UV‑stabilized tapes and inks keep color fast; coated faces and liners resist humidity; anti‑slip back panels maintain stack angles under vibration and wrap tension.

Compliance & safety. Food‑adjacent goods demand polymer declarations and migration testing; hazardous powders may require UN‑rated FIBCs (13H series) and electrostatic classes (Types A/B/C/D). Document labels, SWL/SF for FIBCs, and ensure operator training.

Synthesis. The integrated spec for Industrial Packaging Bags sets mesh/GSM (or film gauge), coating/lamination, liner thickness, seam architecture, COF ranges, print method, and labeling—so every stakeholder reads the same one‑page truth.

Materials and Constructions Used in Industrial Packaging Bags

Woven polypropylene (PP). Oriented PP tapes woven into fabric, often coated or laminated. Strength‑to‑weight is excellent; edges stitch cleanly; surfaces take print beautifully when laminated with BOPP. Common in 25–50 kg sacks and dominant in FIBCs.

Polyethylene (PE) films. Blown or cast monolayer or co‑extruded films. Useful where transparency, sealability, and simple FFS operation are paramount. Reinforce with thickness, gussets, and anti‑slip when pallet stability is critical.

Multiwall paper. Renewable aesthetic and high stiffness in dry conditions; loses wet strength without PE coating or inner liners. Works in dry climates and short routes; less forgiving in monsoon yards.

Hybrid laminates. PET/PE or BOPP/PE systems offer graphics and sealability but complicate recycling in some regions. When possible, mono‑polyolefin designs for Industrial Packaging Bags simplify scrap handling.

FIBCs (bulk bags). Large woven PP bodies with four lifting loops; optional baffles for cube retention; liners for fines or barrier; electrostatic classes for powder safety. SWL 500–2,000 kg with safety factors 5:1 (single trip) or 6:1 (reusable), and 8:1 for heavy duty.

Manufacturing Workflows Across Bag Types

Woven PP route. PP resin → tape extrusion and slitting → orientation → weaving (circular/flat looms) → coating/lamination → printing (reverse gravure or CI‑flexo) → conversion (cut, gusset, stitch or heat‑seal) → optional liners → inspection and packing.

Film bag route. Polymer extrusion (blown/cast film) → printing → bagmaking (side‑seal, bottom‑seal, or FFS tubing) → venting/antistatic as needed → palletization.

Paper sack route. Kraft paper plies → tubing → valve formation → optional PE coating/film lamination → print → pallet.

At each step, Industrial Packaging Bags benefit from disciplined controls: corona dyne levels for ink anchorage, adhesive bond strength checks, seam pull tests, and roll‑build management to prevent telescoping.

Performance Metrics: How Industrial Packaging Bags Earn Their Keep

Tensile & tear. Fabric mesh and tape orientation set directional strength; film gauge and modulus tune elongation and seal peel. Bags must withstand clamp forces, drops, and corner impacts without catastrophic failure.

Puncture & abrasion. Sharp granules and pallet edges are unforgiving. Laminated faces raise rub life; denser weaves resist needle tears; anti‑sift seams block fines.

Barrier & cleanliness. Liners reduce dusting and moisture ingress; coated faces shed rain and keep surfaces scannable. For odor‑sensitive products, specify co‑ex liners with barrier layers.

Friction & stackability. Panel‑wise COF tuning lets lines run fast and pallets ride safely. A back panel with higher static COF curbs slip; a lower‑COF face eases machine travel.

Print durability. Reverse‑printed film traps inks under a protective skin; matte finishes scatter scrapes; barcode quiet zones remain clean, enabling automated receiving.

Use Cases: Where Industrial Packaging Bags Prove Themselves

Chemicals and polymer resins. Pellets and powders demand dust control, traceable labels, and consistent bag mouth geometry. Industrial Packaging Bags with coated fabric and form‑fit liners protect material quality and housekeeping.

Fertilizers and soil amendments. Hygroscopic goods cake under humidity. Coated fabrics plus 60–80 μm liners and anti‑sift seams reduce caking and improve downstream flow.

Cement, fly ash, and mineral fillers. Dense, abrasive products punish weak seams. Heavy‑duty woven PP sacks and FIBCs with reinforced bottoms and baffles handle repeated forklift contact and clamp pressure.

Agricultural commodities and seeds. Breathability versus barrier is a balancing act. Select coatings judiciously, and keep graphics legible for seed certification marks.

Food ingredients and food‑aid. Where human consumption is involved, Industrial Packaging Bags should be paired with food‑contact compliant resins and inks placed behind films; labels must survive long routes and rough handling.

Mining and construction logistics. FIBCs move ton‑loads safely, collapse for backhaul, and cut tare mass. Discharge spouts and vibration frames speed unloading at batch plants.

Problem → Solution → Result: Three Industrial Scenarios

Scenario 1 — Fine pigment, 50 kg sacks.

Problem: Dust escaping at stitch lines; rub‑off of hazard diamonds; pallet slip in humid yards.

Solution: Coated woven PP sacks with form‑fit liners; anti‑sift seams; reverse‑printed BOPP matte face; back‑panel anti‑slip.

Result: Cleaner baghouses, readable labels on arrival, fewer rewraps, and a measurable drop in credits.

Scenario 2 — Hygroscopic fertilizer, 50 kg sacks.

Problem: Caking during monsoon season; split bottoms after clamp handling.

Solution: Raise coating mass; adopt double‑stitched bottoms with inner folds; specify 60–80 μm liners with tie‑off; document clamp pressure limits.

Result: Lower caking complaints, higher line speed at destination, longer safe stack dwell.

Scenario 3 — Mineral filler, 1,000 kg FIBCs.

Problem: Leaning stacks and residual product after discharge.

Solution: Baffle FIBCs (90×90×110 cm) with conical spout, loop height matched to forks, and anti‑sift seams; operator SOP for discharge frame and vibrator.

Result: Tighter pallet cubes, fewer load shifts, residuals cut from ~2% to <0.5%.

Horizontal Thinking: Where Disciplines Meet Inside Industrial Packaging Bags

Color science’s LAB targets intersect with scanner physics: rich solids must still deliver barcode contrast. Tribology (the science of friction) shapes anti‑slip coatings; palletizer mechanics translate those coatings into real‑world stack behavior. Polymer chemistry informs tape orientation in woven fabrics; that orientation determines seam architecture; seam architecture dictates drop survival; drop survival protects production schedules. Cross‑domain fluency makes Industrial Packaging Bags robust without over‑engineering.

Vertical Thinking: From Molecule to Pallet, Cause to Effect

Follow the chain. Resin MFI affects tape drawability; drawability sets tenacity; tenacity plus mesh yields fabric modulus; modulus plus coating mass defines crease memory and mouth stiffness; stiffness governs filling speed and seal quality; seal quality secures pallets; pallets determine transport risk and customer satisfaction. A small tweak upstream can cascade into large savings downstream. That is why Industrial Packaging Bags should be specified with both microscope and telescope in hand.

Testing, Standards, and What to Put in the Spec Sheet

A defensible program for Industrial Packaging Bags lists: bag dimensions and tolerances; fabric mass and mesh (or film gauge); coating/lamination mass; liner gauge and style; seam type and stitch pitch; COF targets by panel; print method and ΔE* tolerances; UV stabilization hours where relevant; and required tests (COF, rub, tensile, drop, top‑lift for FIBCs, stacking, tilt, discharge). Document SWL/SF for bulk bags and any UN or electrostatic classification.

Tests commonly requested include water‑vapor transmission rate (WVTR), oxygen transmission (where needed), Sutherland rub for print durability, static/kinetic COF, free‑fall drop, seam pull, xenon‑arc lightfastness, and FIBC top‑lift. The point is not to decorate the spec with acronyms; the point is to connect tests to risks you actually face.

Safety and Electrostatics: When Powders Behave Like Storm Clouds

Powders can accumulate charge; discharges can ignite flammable atmospheres. Industrial Packaging Bags in FIBC form are categorized by electrostatic behavior: Type A (no protection), Type B (limits brush discharges), Type C (conductive grid requiring grounding), and Type D (static‑dissipative without a ground lead). Choose based on your product’s minimum ignition energy and plant zoning. Train operators, inspect grounding clamps, and don’t mix bag types without signage and SOPs.

Sustainability and End‑of‑Life: Credible Claims for Industrial Packaging Bags

Lightweighting saves resin; mono‑polyolefin designs simplify recycling where PP/PE streams exist; post‑industrial scrap can be reprocessed when contamination is controlled. Avoid universal promises; state the structure, the design rule followed, and the markets where the claim applies. If you use recycled content, keep chain‑of‑custody documents; if you claim recyclability, align inks and adhesives with the target stream. Real sustainability for Industrial Packaging Bags is cumulative: grams saved plus hours saved plus spills avoided.

Implementation Playbook: From RFQ to First‑Pass Yield on Industrial Packaging Bags

1. Duty definition. Record product density, particle shape, flowability, moisture sensitivity, route climate, clamp and fork handling, desired pallet stacks, and dwell times.

2. Platform choice. 50‑kg PP woven sacks versus film FFS versus multiwall paper versus FIBCs; many sites run a mix. Let product duty and line speed decide.

3. Structure engineering. For woven PP: choose mesh/GSM and coating mass; for films: set gauge and seal geometry; for FIBCs: pick body style, baffles, loop height, spout type, liner, and electrostatic class. For all: define seam type and stitch pitch.

4. Friction and finish. Set COF targets per panel; deploy anti‑slip lacquers and micro‑texture strategically; match finish (matte/gloss) to scanner glare and branding needs.

5. Color and codes. Provide Pantone references for solids, LAB targets and tolerances, barcode specs and quiet zones, and QR/serialization rules.

6. Qualification plan. Run line trials at target BPM; perform drop/stack tests under humidity expected on route; verify rub life on worst‑case solids; top‑lift and discharge tests for FIBCs; document outcomes.

7. QA governance. Create incoming checks (fabric mass, liner thickness), in‑process controls (bond strength, corona dyne), and finished‑goods audits (dimensions, seams, COF, print ΔE*). Lock change‑control for inks, adhesives, and fabric suppliers.

8. Training & SOPs. Grounding for Type C bulk bags; safe discharge sequences; pallet patterns and wrap recipes; clamp pressure limits; label reading for operators.

9. Continuous improvement. Track BPM, micro‑stop minutes, rewrap rates, spill incidents, credit memos, and energy mix. Feed lessons learned back into the spec for the next lot of Industrial Packaging Bags.

Frequently Asked Questions About Industrial Packaging Bags

Q: Are Industrial Packaging Bags compatible with high‑speed baggers?

A: Yes—when friction windows are specified by panel and mouth geometry fits the former. Reverse‑printed films improve glide without sacrificing graphics.

Q: Will prints and barcodes survive long routes?

A: Reverse printing under film, matte topcoats, and defined rub test limits keep information readable. Protect quiet zones and use high‑contrast palettes.

Q: How do I choose between sacks and FIBCs?

A: Consider SKU counts, batch sizes, handling infrastructure, and hygiene. Industrial Packaging Bags in sack form excel for high counts and fast lines; FIBCs shine for forkliftable bulk with fewer changeovers.

Q: Are these bags recyclable?

A: Many designs use mono‑PP or mono‑PE structures that align with PP/PE streams. Verify local infrastructure; specify compatible inks and adhesives; disclose structure on pack.

Q: What is the single biggest cause of failure?

A: Mis‑matched specs—too little coating, the wrong stitch pitch, no anti‑sift seams, or COF out of window. A one‑page, cross‑functional spec for Industrial Packaging Bags prevents most surprises.

Introduction: Defining Industrial Packaging Bags

Industrial Packaging Bags are engineered containers designed to protect, identify, and move bulk solids across stressful supply chains. Built from woven polypropylene, polyethylene films, multiwall paper, or composite laminates, Industrial Packaging Bags must resist tearing, puncture, humidity, abrasion, and mishandling while remaining readable for barcodes and hazard marks. You will also see them described as bulk sacks, industrial woven bags, heavy‑duty PE bags, multiwall paper sacks, and FIBCs/Jumbo bags—different names for a common mission: safe, efficient containment at scale. Typical uses include chemicals and resins, fertilizers and soil amendments, mineral fillers and cement, salt and sugar, grains and seeds, and food‑aid logistics. For an overview of PP‑woven formats widely used in industry, visit Industrial Packaging Bags.

Problem Orientation: What Pain Points Do Industrial Packaging Bags Solve?

Factories face a stubborn cocktail of risks: powders dust through stitch holes; sacks slip on pallets; graphics scuff until safety icons fade; tropical humidity cakes hygroscopic materials; clamp trucks bruise corners; scanners fail on low‑contrast codes. Industrial Packaging Bags address these problems as a system rather than a patchwork—mechanical strength prevents ruptures, barrier choices control moisture and dust, friction windows stabilize stacks, and protected print preserves traceability. The backdrop is harsher than retail packaging: more weight, more touches, more weather, more consequences when something fails.

Method: Building a Specification for Industrial Packaging Bags

A credible method starts with decomposition. First, define containment physics: tensile, tear, puncture, seam strength, and drop survival relative to density and route. Second, design the surface and structure: fabric mesh and GSM for woven PP, or film gauge and seal geometry for PE; coating or lamination mass for dust and water resistance; liner thickness for barrier or cleanliness. Third, govern friction: target a lower static/kinetic COF on the machine‑facing panel and a higher COF on the pallet‑facing panel so Industrial Packaging Bags glide through the former but lock in transit. Fourth, protect information: reverse printing under film or shielded print windows, Pantone/LAB color control, and adequate barcode quiet zones. Fifth, integrate compliance: food‑contact declarations, electrostatic classes for bulk bags, UN codes for dangerous goods, and clear labels for SWL/SF where FIBCs are involved.

Result: Line Throughput, Logistics Stability, and Cleaner Arrivals

When the method is executed, results are visible in production dashboards and receiving docks. Line speeds rise because bag mouths stay square and friction is in range; micro‑stops fall as sacks track straight and do not snag; pallets travel without leaning because back panels grip and baffles (on bulk bags) hold shape; warehouses stay cleaner because anti‑sift seams and liners contain fines; and customers accept loads because hazard diamonds and barcodes remain legible. Industrial Packaging Bags stop being an afterthought and start looking like a quiet competitive edge.

Discussion: Why the Method Works for Industrial Packaging Bags

The logic holds because each lever speaks to a real failure mode. Mesh, GSM, and tape orientation resist propagation of tears; lamination stiffens faces and shelters inks; COF windows convert tribology into predictable machine behavior; liners decouple the product from ambient humidity; electrostatic classes prevent dangerous discharges during filling and discharge. Horizontal thinking—color science meeting scanner physics, friction chemistry meeting palletizer mechanics—ensures choices complement one another rather than conflict. Vertical thinking—molecule to pallet—keeps cause and effect aligned: resin MFI affects tape drawability, which sets tenacity, which dictates seam design, which governs drop survival, which determines stack height.

System Decomposition: Sub‑Problems Inside Industrial Packaging Bags

Consider five nested sub‑problems. Containment: the bag must not burst, leak, or wick. Cleanliness: dust must stay inside and labels must remain readable. Operability: sacks must run at target BPM with minimal operator intervention. Logistics: pallets must stack, resist slip, and survive clamp pressure. Compliance: materials, markings, and test results must pass audits. Each sub‑problem has a precise lever—fabric mass, liner gauge, seam pitch, COF targets, and print protection—and Industrial Packaging Bags unify them into one spec that purchasing, operations, safety, and quality can all sign.

Horizontal Thinking: Cross‑Domain Links That Improve Outcomes

A barcode that scans at 3 a.m. in a humid port owes its success to design upstream. Reverse printing under film preserves contrast; matte finishes reduce glare; Pantone solids with LAB tolerances limit color drift; high‑COF backs resist the vibration that rubs ink away. Meanwhile, palletizer algorithms meet chemistry when anti‑slip coatings hit stretch‑wrap tension; operations research meets packaging when base sizes and baffles maximize container cube. Industrial Packaging Bags prosper when these conversations happen early, not after a complaint.

Vertical Thinking: From Polymer Chain to Pallet Pattern

Follow one thread. If resin MFI is poorly chosen, tapes cannot draw; if tapes cannot draw, tenacity drops; if tenacity drops, seam allowances must increase; if seams change, bag mouths deform; if mouths deform, formers jam; if jams occur, operators cut speeds and add rework. A different thread: increase coating mass slightly, and rain beading improves; improved beading cuts water absorption; lower moisture keeps COF stable; stable COF preserves stack geometry; preserved geometry reduces rewraps and load refusals. In Industrial Packaging Bags, small upstream changes echo loudly downstream.

Customization: Dimensions, Structures, and Artwork for Industrial Packaging Bags

Customization is a performance tool, not a vanity feature. Widths around 48–56 cm and heights around 86–95 cm dominate 50‑kg sacks; a common footprint is 55×95 cm for dense powders. Fabrics span 70–120 g/m² with 10×10 to 14×14 meshes depending on duty; liners range from 30–80 μm where dust or moisture control is required. For ton‑level Industrial Packaging Bags in FIBC form, base sizes near 90×90×100–120 cm with SWL 500–2,000 kg and SF 5:1 or 6:1 are commonplace. Artwork should be planned for 360° storytelling while reserving clean zones for regulatory marks and scannable codes. Numbers, not adjectives, keep brands consistent across suppliers.

Operations: Throughput and Stability Without Guesswork

Bagging lines favor predictability. By specifying static and kinetic COF bands for the machine face and pallet face, Industrial Packaging Bags slip where they should and hold where they must. Reverse‑printed graphics survive contact with rails, chutes, and cartons; double‑stitched bottoms or pinched seams maintain integrity under clamp pressure; baffles in bulk bags keep low‑density powders cubed and stable. When performance drifts, a one‑page spec with COF, ΔE*, seam pull, and drop targets makes root cause analysis faster than trial‑and‑error tinkering.

Sustainability and End‑of‑Life: Credible, Verifiable Paths

Lightweighting reduces resin use per unit; mono‑polyolefin structures simplify recycling where PP/PE streams exist; post‑industrial scrap can be reprocessed when contamination is controlled; UV‑stable inks and durable finishes extend display life and reduce waste. Credibility matters: Industrial Packaging Bags should state structure and intended stream, align inks and adhesives with that stream, and avoid blanket claims that ignore regional infrastructure. Real progress is measured—in grams saved, spills avoided, rewraps reduced, and energy mix improved.

Implementation: From RFQ to First‑Pass Yield on Industrial Packaging Bags

Begin with a duty brief: density, particle size, moisture sensitivity, route conditions, clamp handling, stack height, and dwell times. Choose the platform—woven PP sacks, film bags, paper sacks, or FIBCs—based on hygiene, speed, and handling infrastructure. Engineer structure and finish: mesh/GSM and coating mass, liner gauge and style, spout or valve formats, and panel‑wise friction. Govern color and codes with Pantone lists, LAB targets, and quiet‑zone rules. Qualify with drop, rub, COF, seam pull, and (for FIBCs) top‑lift and discharge tests under realistic humidity and temperature. Lock change‑control for inks, adhesives, and fabric suppliers so that approved performance stays approved.

Ordering and Scale‑Up: Turning Specs Into Supply

A workable procurement plan pairs a tight spec with a flexible supply base. Dual‑source critical components like films and liners; approve multiple dielines for different fillers; keep label and barcode templates synchronized; and audit roll build and splice maps so line starts stay smooth. As volumes grow, standardize on dimensions that maximize pallet cube and container utilization. Direct teams to the canonical spec and resource page here: Industrial Packaging Bags.

References

ISO 21898 — Packaging — Flexible intermediate bulk containers (FIBCs) for non‑dangerous goods: requirements and test methods.

IEC 61340‑4‑4 — Electrostatics — Standard test methods for specific applications — Electrical resistance and charge decay of FIBC materials.

ASTM D1894 — Standard Test Method for Static and Kinetic Coefficients of Friction of Plastic Film and Sheeting.

ASTM F1249 — Standard Test Method for Water Vapor Transmission Rate Through Plastic Film and Sheeting Using a Modulated Infrared Sensor.

ASTM D5276 — Standard Test Method for Drop Test of Loaded Containers by Free Fall.

GB/T 8946‑2013 — Woven bags of polypropylene or polyethylene — General technical requirements.

EN 277 — Sacks for the transport of foodstuffs — General requirements and test methods.

RecyClass — Design for Recycling Guidelines for PP and PE flexible packaging.

CEFLEX — Designing for a Circular Economy (D4ACE) Guidelines for Flexible Packaging.