What Are FIBC Bulk Bags and Why Do They Behave Like Equipment?

A plant rarely “buys a bag.” A plant buys time, safety, cleanliness, and predictability—then hopes the bag will quietly deliver those outcomes. That hope is exactly why FIBC Bulk Bags deserve to be described as a load-bearing system rather than a packaging accessory. They are flexible industrial containers built to move dry bulk materials—powders, granules, flakes, and small aggregates—at a scale that ordinary sacks cannot handle. In many workflows, one unit is expected to carry hundreds of kilograms to a couple of metric tons. That single fact changes everything. When the unit load becomes large, the cost of a mistake becomes large; when the cost of a mistake becomes large, design stops being cosmetic and becomes operational.

So what is a well-designed FIBC Bulk Bag? It is not “a bigger bag.” It is a repeatable handling module—something that can be filled efficiently, lifted safely, stacked predictably, transported through vibration and weather, and discharged without turning product into dust or turning a warehouse into a cleanup project. In the real world, the bag meets forklifts, cranes, pallets, hooks, conveyor edges, container walls, and human habits. Some of those forces are controlled; many are not. A bag that performs only in ideal conditions is a bag that fails in normal conditions.

Key idea — The “bag” is a system: fabric + seams + lifting loops + top/bottom interfaces + optional barrier layers. Change one element, and the whole system’s behavior can shift—during filling, under braking, under compression, and under aging.

Because different regions and departments use different vocabulary, FIBC Bulk Bags are known by many aliases. Procurement may search one phrase; operations may speak another; a safety officer may insist on a third. The product family is the same, but the language differs. Common market aliases include:

- FIBC Bags

- Flexible Intermediate Bulk Container Bags

- Jumbo Bags

- Big Bags

- Ton Bags

- Bulk Bags

- FIBC Jumbo Bags

Throughout this text, the main phrase remains FIBC Bulk Bags, while long-tail expressions appear naturally—food-grade FIBC bulk bags, baffle FIBC bulk bags, anti-static FIBC bulk bags, UN-certified FIBC bulk bags, and FIBC bags for cement. The reason is practical: the same platform must solve different problems, and people name products by the problem they need solved.

The Material System of FIBC Bulk Bags: Start With Physics, Not Shape

If you want to understand why FIBC Bulk Bags are versatile, do not begin with the silhouette. Begin with materials, then ask a more demanding question: where is each material placed, and what job does that placement perform? A bulk bag is a layered material system. The woven body provides primary strength, yes—but containment quality, stacking stability, and handling predictability depend on the whole bill of materials and, more importantly, on how those materials interact at seams and interfaces.

Strength begins with oriented PP tapes and ends at seam and loop interfaces.

Containment is rarely “one feature”; it is a chain: weave + coatings/liners + seams + closures.

You can think of FIBC Bulk Bags as engineered textiles with optional barrier behavior. That framing matters because it changes how you specify them. Instead of asking, “Is it strong?” you start asking, “Strong where, in what direction, after which handling, and for how long?” Instead of asking, “Is it leak-proof?” you begin asking, “What is the leakage probability under vibration, with this particle-size distribution, at this humidity?” The second set of questions is harder. It is also the set of questions that prevents expensive surprises.

Core Polymer: Polypropylene Tape Fabric and the “Hidden” Strength of Orientation

Most FIBC Bulk Bags are built from woven polypropylene (PP). It is easy to say “polypropylene” as if the story ends there, but it does not. PP becomes high-performance not simply because it is a polymer, but because it is processed into a structure that carries load efficiently. The transformation is both chemical and geometric: PP resin becomes film, film becomes slit tapes, tapes are drawn so polymer chains align, and aligned tapes are woven into a lattice that distributes stress. A lattice behaves differently than a sheet. Under shock and vibration, it can share load across many intersections rather than concentrating stress along one tear path.

Here is an uncomfortable truth that improves procurement discipline: resin price is not the only cost. Variation is a cost. A bag program with inconsistent resin or inconsistent drawing control does not create one predictable product; it creates a distribution. Some units are strong, some are weak. And in real logistics, the warehouse pays for the weak tail, not the average. This is why many industrial programs prefer consistent virgin PP supply for critical applications, and why process stability upstream matters long before the bag is sewn.

A question worth repeating—because repetition is sometimes the most honest rhetoric: if two FIBC Bulk Bags look similar on paper, but one has controlled tape orientation and the other does not, are you buying the same product… or the same risk?

Fabric Architecture: Weave Density, Yarn Fineness, and the Containment–Breathability Trade

Versatility often begins with trade-offs, and woven PP is no exception. A woven structure naturally has tiny interstices. For coarse granules, those gaps may be irrelevant. For fine powders, they can become leakage paths. That is why weave density and construction details matter. Denser weaves typically reduce sifting but can influence stiffness, forming behavior, and even air venting during filling. Finer yarn approaches can increase flexibility and improve fold performance, but they require consistent control to keep tear and puncture margins intact. The fabric is not merely “strong.” It is tuned: tuned for the material, tuned for the route, tuned for the workflow.

Practical lens — For FIBC Bulk Bags, containment is a probability problem. The smaller the particles and the longer the vibration exposure, the more aggressively the material behaves like a fluid seeking gaps. The best specifications assume that behavior instead of being surprised by it.

Optional Functional Layers: Coatings, Laminations, and Liners as Modular Tools

One reason FIBC Bulk Bags travel across so many industries is their modularity. The woven skeleton can remain similar while optional layers change the bag’s behavior. A compatible PE coating can reduce sifting and improve moisture resistance. A BOPP lamination can protect printed surfaces and add scuff resistance. Liners—often polyethylene or specialized barrier films—can turn a breathable woven container into a barrier-oriented system. That sounds straightforward until you remember that every new layer changes filling dynamics, discharge behavior, and even static behavior. A liner is not “just an insert.” It affects air displacement, can cling during discharge, and can shift how dust migrates inside the unit load.

Surface layers also affect friction. A bag that is too slippery can shift under truck braking; a bag that is too grippy can drag on conveyors and slow handling. The right surface is not a moral victory. It is an engineering target, usually expressed as a controlled range rather than a vague promise.

Coating

Lower sifting, better moisture resistance, altered friction.

Lamination

Print protection, scuff resistance, tuned surface behavior.

Liner

Barrier containment, hygiene support, fine powder control.

Secondary Materials: Threads, Tapes, Loop Components, and the Tyranny of Interfaces

If failures had a favorite address, they would live at interfaces. Needle perforations at seams. Loop stitching zones. Corner stress concentrations. Spout attachments. These are the places where a large, flexible unit load transforms internal forces into external handling events. That is why thread type, stitch pattern, stitch density, and reinforcement tapes are not “small decisions.” They are decisions about load path. A strong fabric cannot rescue an under-designed loop zone. A beautiful lamination cannot rescue a seam recipe that migrates under vibration. In FIBC Bulk Bags, the weakest link tends to declare itself suddenly—often when the consequences are messy and expensive.

Additives and Environment: UV Stability, Slip Control, and Electrostatic Management

Versatility also means surviving different environments. Outdoor storage demands UV stabilization. High-speed handling may need slip/anti-block tuning. Powder environments may need electrostatic risk management. Electrostatic behavior is not a marketing category; it is a safety category. Many operations describe electrostatic variants in a familiar type-language (often Type A, Type B, Type C, and Type D) to clarify whether grounding is required and what discharge behavior is expected. The point is not to memorize labels; the point is to align the bag type, the product, and the operating rules so that a good design does not become an unsafe workflow.

Safety reminder — The safest bag can become unsafe if used incorrectly. If a design requires grounding, the workflow must make grounding routine, visible, and non-optional.

Key Features of FIBC Bulk Bags as Operational Levers

Feature lists are cheap. Operational outcomes are expensive. So let’s translate the features of FIBC Bulk Bags into the consequences that plants actually experience: fewer handling events, fewer spills, less dust, more predictable stacking, and clearer compliance alignment. The logic is almost paradoxical: scale reduces the number of units, which can reduce handling steps, yet scale increases the consequence of any single failure. This is why conservative engineering around seams and loops matters more than decorative features.

High payload per unit

Fewer sacks, fewer scans, fewer interfaces to fail—yet higher consequence per incident.

Lift-loop architecture

The bridge between packaging and equipment; it defines the load path and the risk path.

Loops deserve special attention because they translate fabric strength into liftable geometry. Standard corner loops, cross-corner loops, and sleeve loops exist because equipment interfaces differ and workflows differ. But the deeper question is always the same: when lifted, where does the load go? Does it concentrate at a stitch line? Does it spread into the body fabric? Does it create torsion that stresses corners? A loop style is not merely a choice; it is a load-path decision with safety consequences.

Containment, meanwhile, is a chain: weave density reduces pathways through fabric; coatings and laminations close pathways further; seam construction protects the stitched line; and top/bottom closures control dusting during filling and discharge. When someone asks, “Is it leak-proof?” the most honest response is a question: “Under which conditions?” Because vibration, particle size, humidity, and handling intensity can turn “fine” into “failure” with surprising speed.

How FIBC Bulk Bags Are Made: Control the Chain, Not the Finale

A reliable FIBC Bulk Bag is produced through a controlled chain. Final inspection can catch defects, but it cannot erase upstream variability. The most useful way to explain manufacturing is to divide it into three phases: upstream raw-material selection and incoming inspection; midstream manufacturing and converting steps; and downstream quality inspection, testing, and release discipline. If one phase is weak, the next phase inherits the problem. Variation does not disappear; it migrates.

Upstream Control: Raw Material Selection and Incoming Verification

Upstream control is not paperwork; it is an early warning system. For FIBC Bulk Bags, incoming resin consistency influences extrusion stability, tape thickness uniformity, drawing behavior, and ultimately fabric performance. Incoming checks often focus on processing consistency and traceability. Additives are verified to match the environment—UV stabilizers for outdoor storage, friction-control packages for handling stability, electrostatic packages when required. When liners are used, incoming film checks focus on thickness uniformity and seal behavior. A liner that varies in thickness becomes a barrier that varies in performance; a barrier that varies becomes a complaint waiting for the wrong weather.

Why traceability matters — When something fails in the field, the fastest path to root-cause analysis is lot-level documentation: resin lot, tape lot, fabric lot, liner lot, and finished-bag lot linked together.

Midstream Manufacturing: From Resin to Fabric to Bag

The midstream story is not romantic, but it is decisive. PP resin is melted, filtered, and extruded into film; film is slit into tapes; tapes are drawn to align polymer chains; oriented tapes are woven into fabric; fabric may be coated or laminated; fabric is cut; panels are prepared; seams and loops are assembled; optional spouts, baffles, and liners are integrated; printing and markings are applied; and finally the bag is finished with controlled inspection gates. Each step carries its own failure modes. Each step also carries its own controls. The goal is not perfection in one step. The goal is stability across steps.

Tape drawing deserves special emphasis because it is the quiet foundation of performance. Over-drawing can create brittle tapes prone to splitting; under-drawing can leave strength unused. Weaving control then translates tape discipline into fabric discipline—warp/weft balance, weave density, edge stability, and weight tolerance. If coatings or laminations are added, interface stability becomes critical: bond consistency, thickness stability, and web handling control determine whether the surface performs in real handling or delaminates under stress.

Repetition with purpose: when large bulk bags fail, they often fail where they were stitched—or where interfaces were asked to carry loads without sufficient reinforcement.

Downstream Discipline: Inspection, Testing, Sampling, and Release

A disciplined program uses layered inspection: incoming checks to stop bad inputs; in-process checks to stop drift; finished-goods checks to confirm dimensions and workmanship; and sampling plans to detect slow changes over time. Finished checks often include seam integrity sampling, loop attachment integrity checks, dimensional verification, visual inspection for contamination or defects, and program-specific tests when needed. For hazardous goods applications, additional regulatory frameworks and certification practices may apply, making documentation and controlled testing even more important. The objective is simple to state and hard to achieve: a stable distribution of outcomes across long production runs.

Applications of FIBC Bulk Bags: Grouped by Dominant Risk, Not by Industry Buzzwords

A flat list of industries is easy to write and easy to forget. A risk-based map is harder to write and easier to use. FIBC Bulk Bags are deployed wherever scale, efficiency, and controlled handling intersect—but their design priorities change depending on what risk dominates. Is abrasion the enemy? Is dust the enemy? Is moisture the enemy? Is documentation the enemy? Each enemy demands different countermeasures.

Abrasive & heavy

Cement, aggregates, minerals: prioritize reinforcement, abrasion tolerance, loop stability.

Fine powders

Talc, additives: prioritize sift resistance, seam strategy, dust-controlled discharge.

Moisture sensitive

Gypsum blends: prioritize barrier strategy matched to route and condensation risk.

Food-adjacent

Ingredients: prioritize hygiene, declarations, contamination control, traceability.

A paradox is worth stating clearly: more barrier is not always better. If you block moisture ingress but trap condensation, you can create a different quality problem. This is why route context matters. A bag that performs flawlessly in a temperate warehouse may struggle on a long, humid route. And a bag that is perfect for short dwell times may be wrong for long outdoor storage. In other words: the product matters, but the route can dominate.

How VidePak Controls and Guarantees Quality for FIBC Bulk Bags

Quality should be described the way operations experience it: fewer surprises. Fewer ruptures. Fewer leaks. Fewer claims. VidePak’s approach can be explained as a stepwise system rather than a single inspection moment—because field failures rarely come from one isolated error. They come from weak links. The strategy below emphasizes mainstream standards, consistent virgin materials, premium equipment stability, and a complete inspection loop.

Step 1 — Standards-driven production and verification

Bags are produced and tested using mainstream frameworks (such as ISO, ASTM, EN, and JIS), so test methods, sampling logic, and acceptance language remain consistent across production and qualification.

Step 2 — Virgin raw materials from major suppliers

Virgin PP and controlled inputs reduce contamination risk and reduce variability, especially in tape extrusion and fabric consistency. The goal is not ideology; it is tighter performance distribution.

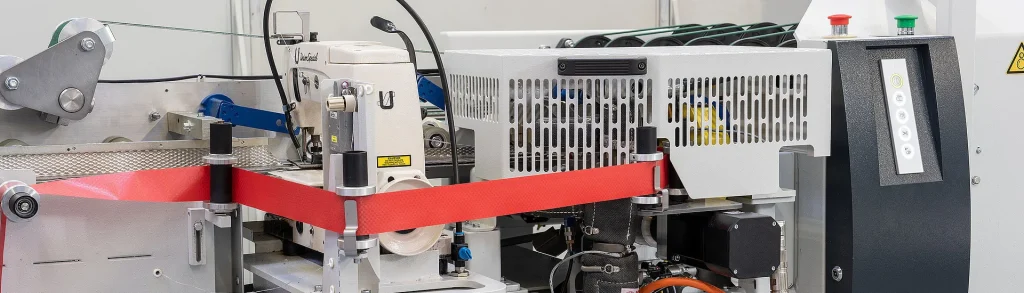

Step 3 — Premium equipment as variation-reduction

VidePak emphasizes that its core equipment platform is from Austrian Starlinger and German W&H, because stable extrusion/weaving and stable printing/converting reduce drift and improve repeatability.

Step 4 — Complete inspection loop

Incoming inspection + in-process inspection + finished-goods inspection + statistical sampling are used to detect drift early and prevent defect migration.

Versatility as Systems Thinking: Decompose Problems, Then Rebuild the Solution

The phrase “versatile” is often used as praise, but in engineering it should mean something stricter: a system is versatile when it can be tuned without becoming fragile. A system is fragile when small changes trigger unpredictable failures. In bulk packaging, fragility is expensive. A single rupture can erase months of unit-price savings; a single dust leak can create repeated cleanup; a single mis-labeled lot can trigger a chain of investigations. So instead of treating versatility as a list of options, treat it as a controllable property. To do that, break real operational problems into smaller sub-problems, then match each sub-problem to design levers.

Sub-Problem Map 1: Containment and Leakage as a Probability Curve

People want a binary answer: leak-proof or not. Reality offers a probability curve. Fine powders behave like fluid under vibration. They migrate. They seek gaps. They find needle holes. They travel along fold channels. If you treat leakage as “on/off,” you will be surprised. If you treat leakage as probability—shaped by particle size distribution, handling intensity, seam strategy, and closure design—you will design more calmly and specify more clearly.

Layered containment usually means layered tactics: reduce gaps in fabric (weave density), reduce gaps at seams (stitch strategy, sealing, bridging), reduce dusting at top/bottom interfaces (closure design), and reduce migration inside (liner strategy, if used). Notice the pattern: no single tactic is enough. The system wins when the chain is strong.

Sub-Problem Map 2: Load Safety as a Workflow Decision

A bulk bag is lifted, and that simple sentence hides dozens of real-world variations: forklift lift versus crane lift; smooth lift versus jerk lift; straight lift versus angled lift; new operator versus experienced operator; short route versus long route; indoor storage versus outdoor yard. Safety margins exist because the lift environment is never perfectly controlled. So the question becomes: what is the cost of being wrong? If the cost is large—safety incident, major spill, regulatory exposure—then conservative margins are rational rather than cautious.

Sub-Problem Map 3: Filling Speed Without Hidden Damage

A bag can be easy to fill and still fail later. Why? Because filling can create micro-damage: abrasion at spouts, impact from product drop, distortion from uneven filling, and internal pressure from trapped air (especially with liners). Here the rhetorical questions are practical, not poetic: Do you want speed that creates a later claim? Or speed that creates a stable unit load? The best programs match top design and venting behavior to the filling method—open top, skirt, duffle, spout—then verify through line trials rather than assumptions.

Sub-Problem Map 4: Discharge Control as Safety, Yield, and Cleanliness

Discharge is where cost can leak out invisibly: dust clouds that require cleanup; uncontrolled flow that creates spillage; partial discharge that cannot be closed cleanly; liner cling that traps product and reduces yield. Bottom spout design, closure behavior, and internal flow control features matter because they transform a bag from “storage” into “dosing.” If the discharge interface is poorly matched to the process, operators will improvise. And improvisation is where safety and consistency degrade.

Sub-Problem Map 5: Shape Control and Space Utilization

Bulging bags waste space and reduce stacking stability. Baffle designs can improve squareness and container cube utilization, but they add complexity and therefore demand process control. This is where systems thinking keeps you honest: performance gains are real, but so are complexity costs. Do you need the cube gain enough to justify tighter controls? If freight is a dominant cost, the answer is often yes. If routes are short and storage is loose, the answer might be no. The right answer is always contextual.

A Colored Parameter Table: Turning Bag Options Into Decision Inputs

Failure Modes and Countermeasures: A Field-First View

Warehouses do not experience “material science.” They experience failure modes. And failure modes usually repeat. Below is a field-first map that connects common failures to root-cause patterns and practical countermeasures. The aim is not to scare. The aim is to focus design energy where it matters.

A Practical Selection Workflow: Specify Like an Operations Engineer

A strong specification is not a wish list. It is a risk map turned into design levers. Start by defining product behavior: fine powder or granule, hygroscopic or not, contamination-sensitive or not, electrostatic risk or not. Then define route and environment: outdoor exposure, humidity cycles, cold routes, long dwell times. Then define handling: forklift intensity, crane lift frequency, stack height, discharge method. Only then should you select bag levers: weave density and fabric weight, seam strategy, liner strategy, top/bottom interface, loop geometry, and surface friction tuning. Finally, verify with trials and tests. If you skip verification, you are not saving time; you are borrowing trouble.

Operational shortcut — Evaluate “cost per successfully delivered kilogram,” not “cost per bag.” A slightly higher unit cost that reduces spills, re-bagging, cleanup, and claims can be cheaper in total cost of ownership.

Connecting Ideas Across Woven Packaging: Useful Internal Reading Paths

If you want to see how related woven-packaging formats solve adjacent problems—breathability, premium printing, barrier composites, valve interfaces, and automated roll applications—these internal reads provide practical context and comparison points:

- How breathable structures balance venting and containment in demanding supply chains

- How BOPP-based formats evolved for durability, clarity, and brand stability

- How multiwall structures manage stiffness, stacking, and handling expectations

- Where barrier composites matter most and how lamination changes performance

- What valve interfaces look like when presentation and speed both matter

- How large-format bags benefit from stronger printing discipline and process control

- How roll-fed automation changes tolerances, throughput, and quality expectations

Sustainability Without Slogans: Reliability as the First Environmental Lever

Sustainability can become abstract, but bulk packaging forces honesty. A rupture creates product waste. A spill creates cleanup waste. A re-bagging event creates packaging waste. So the first sustainability lever is reliability. A slightly stronger, more consistent FIBC Bulk Bag that prevents repeated failures can reduce waste far more than a marginal lightweighting project that increases incident rates. After reliability is achieved, additional strategies become realistic: reducing manufacturing scrap through stable process control; using post-industrial recycled content where performance risks allow; designing components so separation is feasible where local recycling systems exist. But the sequence matters. Reliability first. Material strategy second. Otherwise, the good intention becomes a messy result.

And now a final question—asked as a challenge, not a slogan: if one spill can erase a year of unit-price savings, why keep buying FIBC Bulk Bags as if they were identical?

2026-01-25

- What Are FIBC Bulk Bags and Why Do They Behave Like Equipment?

- The Material System of FIBC Bulk Bags: Start With Physics, Not Shape

- Core Polymer: Polypropylene Tape Fabric and the “Hidden” Strength of Orientation

- Fabric Architecture: Weave Density, Yarn Fineness, and the Containment–Breathability Trade

- Optional Functional Layers: Coatings, Laminations, and Liners as Modular Tools

- Secondary Materials: Threads, Tapes, Loop Components, and the Tyranny of Interfaces

- Additives and Environment: UV Stability, Slip Control, and Electrostatic Management

- Key Features of FIBC Bulk Bags as Operational Levers

- How FIBC Bulk Bags Are Made: Control the Chain, Not the Finale

- Upstream Control: Raw Material Selection and Incoming Verification

- Midstream Manufacturing: From Resin to Fabric to Bag

- Downstream Discipline: Inspection, Testing, Sampling, and Release

- Applications of FIBC Bulk Bags: Grouped by Dominant Risk, Not by Industry Buzzwords

- How VidePak Controls and Guarantees Quality for FIBC Bulk Bags

- Versatility as Systems Thinking: Decompose Problems, Then Rebuild the Solution

- Sub-Problem Map 1: Containment and Leakage as a Probability Curve

- Sub-Problem Map 2: Load Safety as a Workflow Decision

- Sub-Problem Map 3: Filling Speed Without Hidden Damage

- Sub-Problem Map 4: Discharge Control as Safety, Yield, and Cleanliness

- Sub-Problem Map 5: Shape Control and Space Utilization

- A Colored Parameter Table: Turning Bag Options Into Decision Inputs

- Failure Modes and Countermeasures: A Field-First View

- A Practical Selection Workflow: Specify Like an Operations Engineer

- Connecting Ideas Across Woven Packaging: Useful Internal Reading Paths

- Sustainability Without Slogans: Reliability as the First Environmental Lever

Block Bottom Valve Bags (BBVB) are a critical innovation in the packaging industry, particularly in the efficient collection and disposal of various waste types. As a form of Valve Woven Bags, they offer enhanced durability, versatility, and ease of use. The structure of Block Bottom Valve Bags allows for optimal space utilization, making them an excellent solution for transporting and storing bulk products such as waste materials and recyclables.

According to a recent industry analysis, Block Bottom Valve Bags have evolved significantly, offering both environmental and operational advantages. They are increasingly used in waste management and recycling applications, where proper handling of materials like paper, plastic bottles, and other recyclables is crucial. For a more in-depth exploration of how woven bags are evolving within this market, click here to learn more about VidePak’s commitment to woven bag technology.

Structure of Block Bottom Valve Bags

Block Bottom Valve Bags are designed with a flat bottom and a valve opening for efficient filling and sealing. This design enhances their stability and stackability, making them highly efficient for industrial applications, particularly in sectors like construction, agriculture, and waste management.

The valve system simplifies the filling process and can be customized to suit various product needs. These bags are typically produced using polypropylene (PP) and other durable materials, ensuring a long lifecycle and reducing environmental impact. Here are some of the essential components of Block Bottom Valve Bags:

- Block Bottom Structure: The flat bottom design offers superior stability compared to traditional sack designs, enabling easier stacking and handling during transportation and storage.

- Valve Opening: Allows for fast and efficient filling, with various valve options such as tuck-in valves, self-closing valves, and ultrasonic-sealed valves, which reduce spillage and ensure secure closure.

- PP Woven Fabric: High-strength polypropylene woven material enhances the durability of the bag, making it resistant to tears, moisture, and UV exposure.

These structural elements ensure that Block Bottom Valve Sacks are versatile and effective for numerous industrial applications, particularly in waste management where large volumes of material need to be collected, transported, and stored efficiently.

Valve Types and Customization

Block Bottom Valve Bags are versatile in design, featuring different types of valve systems to suit specific operational requirements. The valve type plays a critical role in determining how the bag will be filled, sealed, and handled.

| Valve Type | Description | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tuck-In Valve | The simplest valve type, where the user folds the valve inward after filling. This type is common for lightweight materials. | Suitable for dry materials like cement, chemicals, and some recyclables. |

| Self-Closing Valve | Designed to automatically close after the material is filled. This minimizes product spillage and is ideal for more automated packaging systems. | Typically used for powdered substances and fine granular materials, such as chemicals and food waste. |

| Ultrasonic Sealed Valve | A valve that is sealed using ultrasonic technology, offering a completely sealed bag that prevents leaks and ensures maximum protection of the contents. | Ideal for sensitive materials that require strict containment, such as hazardous waste or moisture-sensitive recyclables. |

Each valve type offers specific benefits depending on the material being handled. For waste management, the self-closing and ultrasonic-sealed valves are often preferred due to their ability to prevent leaks and contain odorous or hazardous waste effectively.

Applications in Waste Management

Block Bottom Valve Sacks are increasingly being employed in waste management and recycling sectors. These bags offer several advantages for handling recyclable materials, hazardous waste, and general refuse. Here’s how they’re commonly used:

- Recyclable Collection:

The robust construction of Block Bottom Bags makes them ideal for collecting and transporting recyclable materials such as paper, plastics, and metals. Their durable, tear-resistant fabric ensures that the bag can handle heavy loads without breaking, even when sharp or bulky recyclables are involved. - General Waste Storage:

Block Bottom Valve PP Bags can also be used for general waste storage, offering a secure, leak-proof option for municipal waste collection. The valve ensures that the bags can be filled efficiently and sealed tightly, preventing odor and spillage during transit. - Hazardous Waste Disposal:

For industrial applications that involve the disposal of hazardous materials, Block Bottom Valve Sacks offer enhanced protection. Ultrasonic sealed valves and moisture-resistant PP fabric make these bags an optimal choice for containing toxic or hazardous substances securely, minimizing the risk of contamination. - Construction Waste Management:

In the construction industry, Valve Woven Bags are used to collect and transport large volumes of construction debris. The high capacity of these bags, combined with their sturdy construction, allows for the efficient handling of materials like cement, bricks, and other heavy debris.

Advantages of Block Bottom Valve Bags in Waste Management

- Durability:

Block Bottom Valve Bags are built to last, with high-strength PP woven fabric that resists tearing, punctures, and moisture damage. This is especially important in waste management, where bags need to withstand heavy loads and rough handling. - Eco-Friendly:

Made from recyclable materials, these bags contribute to sustainability efforts in the waste management industry. They can be reused multiple times before being recycled, reducing the need for single-use plastic bags and minimizing environmental impact. - Cost-Efficiency:

Valve PP Bags are lightweight yet highly durable, which reduces transportation costs due to their lower weight compared to traditional packaging materials. Additionally, their stackable design means more bags can be stored or shipped in a single load, maximizing storage space and cutting logistics costs. - Customizability:

With options for custom printing, sizes, and valve types, Block Bottom Valve Bags can be tailored to meet the specific needs of different waste management operations. Whether for hazardous waste disposal or recyclable collection, these bags can be designed to suit the task at hand. - Enhanced Safety:

In industries dealing with hazardous or toxic waste, the safety provided by the ultrasonic sealed valves is paramount. These bags ensure that potentially dangerous materials are securely contained, protecting both workers and the environment.

Product Parameters of Block Bottom Valve Bags

Below is a table outlining the typical parameters of Block Bottom Valve Bags used in waste management applications:

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Material | Woven Polypropylene (PP), 100% virgin PP |

| Capacity | 25 kg to 50 kg |

| Valve Type | Tuck-In, Self-Closing, Ultrasonic Sealed |

| Dimensions | Customizable, based on client needs |

| Printing | Multi-color, flexographic printing |

| Lamination | Available (BOPP Lamination for moisture resistance) |

| Tensile Strength | High (resistant to tearing and puncturing) |

| UV Resistance | Available (for outdoor waste storage) |

| Reusability | Yes (recyclable and reusable) |

These specifications make Block Bottom Valve Bags highly adaptable for waste management, ensuring that they meet the diverse needs of the industry.

Conclusion

Block Bottom Valve Bags represent an optimal solution for waste management and recycling operations, offering superior durability, versatility, and cost-efficiency. Their customizable design, combined with the ability to handle heavy loads and hazardous materials, makes them a critical component in modern waste disposal systems.

Whether you are looking to manage recyclable materials or hazardous waste, Block Bottom Valve Bags provide the reliability and performance needed to ensure safe and efficient waste collection and transportation. As VidePak continues to innovate in the production of Valve Bags, industries can expect even more advanced features that will streamline waste management processes and enhance environmental sustainability.